Book Review by Martha Nichols

The Rise and Fall of Another Rock Star Bio

RIP, Major Tom

David Bowie, 1947–2016

Liking Bowie was my little secret. In high school, I was a brainy girl, the teachers’ pet, but I went for guys who carried a whiff of danger. I was a geek who wanted to hang with the freaks—especially the ones who whispered in art class about the latest Bowie album, pronouncing it “Boowie,” as if they possessed the key to cool.

Liking Bowie was my little secret. In high school, I was a brainy girl, the teachers’ pet, but I went for guys who carried a whiff of danger. I was a geek who wanted to hang with the freaks—especially the ones who whispered in art class about the latest Bowie album, pronouncing it “Boowie,” as if they possessed the key to cool.

For me, camped on our green plaid couch in the early 1970s—flanked by my silent parents—watching David Bowie perform “Time” on TV was a transformative moment.

He wore a blue jumpsuit with flames over his crotch. He swirled a yellow cape on one arm, amid dancers dressed in spider-webbed leotards. A honky-tonk piano banged along in the background, as Bowie’s wiggling fingers personified Time the Whore, whose “trick is you and me, boy.”

His performance, a mix of vaudeville and Liza Minnelli in Cabaret, flaunted its disregard of the earnest folk and macho guitar rock of the time—and I loved it.

So, when I first glimpsed his backlit image on the cover of Paul Trynka’s David Bowie: Starman (Little, Brown, 2011), I leapt at this new biography, eager to recapture my youth. The shock! The delight! The heat.

But instead of escaping into past thrills, I found myself wanting to escape Trynka’s book. With its relentless chronology of one person’s life, it made me think hard about who reads rock star biographies and why.

Non-fans won’t be hooked by 500-plus pages of Why Bowie Matters. Fans and anyone else who perseveres will find some rewards. The black-and-white photos of young David, decked in every dubious passing fashion, are great, no question. But do even readers like me care about all the details that make a rock star “real”?

Not so much, as it happens.

A Rags-to-Bitches Story

A high-profile biography depends on new research to flesh out a subject’s private life, and in many ways, Trynka is the ideal writer for Bowie’s tale. Former editor in chief of the British music magazine Mojo and author of Iggy Pop: Open Up and Bleed (2008), he reportedly interviewed hundreds of Bowie insiders in writing Starman: ex-bandmates, family members, producers, school buddies, and anyone else who crossed the star’s orbit.

Though he didn’t talk to the Starman himself, Trynka does an impressive job of chronicling Bowie’s every incarnation. Born David Jones in Brixton, South London, the teenage mod renamed himself after knife-wielding frontiersman Jim Bowie, popularized in the 1960 movie The Alamo. As the cult sci-fi rocker Ziggy Stardust, he lived in a swinging Victorian mansion with bisexual wife Angie and their baby Zowie. He leapt from there to cocaine-fueled paranoia, his Thin White Duke persona, and a stint in Berlin. The ‘80s brought movie roles and dance-pop success. In the ‘90s, he married supermodel Iman. He got his teeth fixed. He survived a heart attack in 2004.

Bowie’s initial rise has an inherent momentum that propels the beginning of Starman. In Trynka’s telling, young David comes across as more charming than talented, and the story of how this hip Horatio Alger wills himself to succeed is fun and often funny.

A teenage wannabe lugging around a saxophone, Bowie tried everything and failed; his first record, released when he was still living at home with his mother, sank like a stone. Yet, from the start, Trynka notes, Bowie knew how to attract influential promoters:

David’s discovery of this power was as significant a breakthrough as his improving skills at songwriting. David Bowie had grasped a fundamental truth: before you can be a genius, you have to seem like a genius.

Bowie’s instinct for making waves was indeed a kind of genius. He caused a huge uproar when he declared in a 1972 Melody Maker interview that “I’m gay—and always have been, even when I was David Jones.” (A statement much more shocking in its time than it would be today.) But as Trynka points out, this declaration was well calculated and not necessarily true—or at least, not beyond one wild period that had more to do with Bowie’s ravenous hankering for sex.

In Trynka’s amusing account of this fracas, he says the poor interviewer was clearly “transfixed” by what another writer, Charles Shaar Murray, called Bowie’s “genius for inducing a powerful, platonic man-crush in fundamentally straight guys.”

The Book that Fell to Earth

Starman establishes that Bowie’s talent for fascinating others, combined with his growing musicianship, achieved fiery liftoff in the moment that made him a sensation in Britain: his 1972 appearance on the BBC’s Top of the Pops as Ziggy Stardust, singing “Starman.” Trynka opens his book with the scene:

[E]xcited teens and outraged parents struggle to take in the quilted multicolored jumpsuit, the luxuriant carrottop hairdo, the spiky teeth….

Then Mick Ronson, his Spiders from Mars bandmate, joins the alien at the microphone:

[Bowie] places his arm around the guitarist’s neck and pulls him lovingly toward him. There’s the same octave leap as he sings ‘starman’ again—this time, it doesn’t suggest the bounds of Earth; it symbolizes escaping the bounds of sexuality.

Here, Trynka comes close to evoking what thrilled me as a teenager: Bowie’s arty, campy, subversive refusal to let any boundaries pin him in.

But these evocative moments are too few, crushed as they are by the weight of exhaustive journalistic detail. The dramatic saga of Ziggy Stardust ended in the summer of 1973, when Bowie announced to a tabloid frenzy that he was done with playing Ziggy. A nasty divorce from Angie and financial meltdown quickly followed—and not even halfway through this opus, Starman devolves into a tedious who-said-what.

But these evocative moments are too few, crushed as they are by the weight of exhaustive journalistic detail. The dramatic saga of Ziggy Stardust ended in the summer of 1973, when Bowie announced to a tabloid frenzy that he was done with playing Ziggy. A nasty divorce from Angie and financial meltdown quickly followed—and not even halfway through this opus, Starman devolves into a tedious who-said-what.

The best biographies craft the ungainly sprawl of life into a gripping narrative, one that illuminates a corner of human experience. Otherwise, they founder under a mass of trivia. (The legal wrangles with Bowie’s manager Tony Defries or the demise of Tin Man—just for example—are not riveting.) For a public figure, there’s an obvious arc to the story: birth—struggling in obscurity—success!—disappointment—revelation and/or death. But simply sticking to the chronology is no guarantee of a page turner.

Trynka dutifully includes the kind of titillating highlights that help celebrity bios sell, chronicling groupie combinations, coke binges, and hearsay about Bowie’s “monster dick,” though with a knowing reserve that makes the effort seem a bit bloodless.

Ultimately, even the more entertaining anecdotes undercut the power of Bowie’s story rather than boosting it, bringing it crashing to earth in a most pedestrian way.

Portrait of the Artist as a Starman

Without an absorbing narrative to justify its length, Starman leans heavily on a standard strategy in biographies about artists: staking a claim for its subject’s importance. In his prologue, “Genius Steals,” Trynka makes clear he’s after Bowie’s larger significance. He ups the ante, asking a string of rhetorical questions:

Was the carrot-haired Ziggy, potent symbol of otherness, just an intellectual pose? …[W]as he a showbiz pro exploiting outsiders, like a psychic vampire? Was he really a starman, or was it all cheap music-hall tinsel and glitter?

Trynka highlights Bowie’s clever “lifts” from other musicians like Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, and even Harold Arlen, whose “Over the Rainbow” morphed into the “Starman” chorus. Bowie stole, Trynka says, “with a clear-eyed effrontery as shocking as the lifted melodies.”

Such artistic recycling may be good or bad—plenty of critics keep arguing about that—yet Trynka still seems stuck on using it to explain Bowie as a musical genius. With a fan like me, he’s preaching to the converted; I’m easily convinced that Bowie was an inspiration for the “sampling culture” of the ’80s and ’90s.

But I can’t help thinking of the grand tradition of musical theft before and after Bowie. In Trynka’s quest to be “definitive,” he makes too much of a fuss about this star’s thievery and transformations, comparing him to Dr. Faustus before we reach Chapter One.

Trynka is such an accomplished music critic that I wish he’d just focused on Bowie as a working artist. The sections of Starman that home in on Bowie’s creative process—and the way his collaboration with session musicians and producers influenced the outcome—are insightful, and not just because they identify who came up with specific chord sequences.

Trynka is such an accomplished music critic that I wish he’d just focused on Bowie as a working artist. The sections of Starman that home in on Bowie’s creative process—and the way his collaboration with session musicians and producers influenced the outcome—are insightful, and not just because they identify who came up with specific chord sequences.

Describing “Space Oddity,” Bowie’s first hit, Trynka says it “was born fully formed” in 1968, starting with the first line of the lyrics: “Ground Control to Major Tom.” Bowie composed it with a buzzing Stylophone (a tiny, stylus-operated synthesizer) in the bedroom of a cheap flat he shared with his girlfriend. While some fellow musicians found it underwhelming, Trynka notes:

The song’s distinctive harmonic structure was defined by David’s limited, unconventional guitar style, while its lyrics were tightly plotted. In fact, the piece was not organized like a song, with verses, choruses, and a middle eight; it was more like a work of drama.

He lets us in on Bowie’s offbeat brainstorming (even in 1973, one keyboardist describes Bowie “talking to the brass players using terms like renaissance and impressionist”) and his innovative composing techniques with collaborators like Brian Eno.

In these scenes, Trynka’s subject comes alive on the page in a way that feels different than the usual voyeuristic portrayals of pop stars. But such scenes also fall short of fully conveying why Bowie matters. They don’t get across what connects him to fans: the pure emotional jolt of his songs.

A Total Blam-Blam

The irony of writing about music you love is that it’s like trying to trap smoke in a bottle. Pop music, in particular, gets its hooks into young psyches, providing the sound track for first kisses, first rebellions, first…well, everything that means anything. The music—my music versus your music—conjures teen intensity forever.

That intensity is almost akin to an altered state, which is why so many pop music writers do their best to mimic the heady rush of being there. The language of music reviews is sometimes ludicrously purple but extremely personal—for good reason. Without that connection to the music, the story is incomplete.

Decades ago, I rode my bike around the suburban cul-de-sacs at dusk, listening to “Space Oddity.” Maybe I had a transistor radio; maybe I just sang the words under my breath. Although I doubt this could be true, I remember being completely alone, the sky above me huge and glowing. I remember black birds disappearing into the clouds.

When I think of Bowie now—or better yet, watch those old clips of “Time” or “Starman” on YouTube—it all comes rushing back, the heat, the noise, the shimmer. While writing this review, I’ve been charged up in a way I rarely feel as an adult.

Journalists like Trynka do their best to write around famous subjects by viewing them through the eyes of others, and they can arrive at one form of truth. But the Bowie who emerges by Starman’s epilogue seems disappointingly smaller than life—a cheaply arrayed star let down by his handlers, in hiding, waiting for another chance.

That’s not my Bowie. And it’s not Trynka’s, either, because he held back from giving us his own youthful connection to the music.

Even his opening anecdote about the “Starman” moment that meant so much to British fans is presented impersonally: “Thursday evening, seven o’clock; decadence is about to arrive in five million living rooms.” Trynka narrates from on high, with only an occasional “we” or “us” to hint that he might have been a kid agog at Ziggy, too.

From my perspective, “Starman” was not the big hit in America that it was in the U.K. It was certainly not my favorite song on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. I found it embarrassing, especially the line “let the children boogie,” with Bowie’s inauthentic Brit inflection of “bew-gie.” Even at fifteen and sixteen, I knew he was ripping off American culture, that he was goofily winging it.

But I loved that you could wing it. I felt, in a way I couldn’t yet define, that even if I hated a Bowie song, the strong response it generated in me was a creative spark. For a ’70s girl in California, who very badly wanted to be a writer, it wasn’t just about the lure of kinky sex or his pretty-boy looks or being an outsider. He allowed me to imagine being a boy or girl, grabbing the microphone myself.

The Bowie Archives: One Fan’s Trove

The David Bowie I fell for in the 1970s—so charismatically fey and kitschy—now lives forever online. A highly personal selection of clips, links, and quotes follows. I also recommend Paul Trynka’s “Discography” at the end of Starman, in which his appreciation of the best songs and albums shines through—M.N.

- "Time" on NBC's Midnight Special, 1973.

- "Starman" on the BBC's Top of the Pops, 1972.

- "I Got You, Babe" with Marianne Faithfull on NBC's Midnight Special, 1973.

- "Space Oddity," BBC, 1970.

- Interview with Ellen DeGeneres, April 23, 2004 (during Bowie’s last tour, as a happily married man and father).

- Bowie's Teeth.

Albums and Songs Mentioned in this Review

Albums and Songs Mentioned in this Review

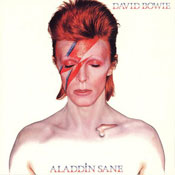

- "Time" on Aladdin Sane, RCA, 1973.

- The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, RCA, 1972.

- "Space Oddity" on David Bowie: Man of Words/Man of Music, Philips, 1969 (re-released as Space Oddity in 1972).

About the "I'm Gay" Interview

- From "Flashback: 22 January 1972" by Michael Watts, the Guardian, January 22, 2006. Watts, the interviewer who got the scoop when Bowie told him he was gay, says his 1972 piece "now reads horribly coy." Three decades later, he recalls the scene:

I met Bowie in his publisher's office, high above Regent Street. He was dolled up as Ziggy, before the world knew of rock stars from outer space. Skintight pantsuit, big hair, huge, red plastic boots—dazzling. Only recently had he stopped wearing a dress—'a man's dress,' he elaborated. He was charming, slightly flirtatious, but made me uncomfortable with myself. 'Camp as a row of tents,' I wrote—did I invent that phrase?—when I wanted to be unmanly and shout: he is unreservedly fabulous.”

About Martha's Favorite Bowie Album

About Martha's Favorite Bowie Album

Aladdin Sane is in some ways a more convincing document on the nature of fame and show business than Ziggy—its flakiness adds authenticity.... [T]he album's great songs are cavernous in their depth, with Mike Garson's rippling piano evoking decadence or oblivion...."

— From David Bowie: Starman by Paul Trynka

See Paul Trynka's website for more about Starman, David Bowie, and Iggy Pop.

Art Information

- “David Bowie bei Rock am Ring 1987″ © Jo Atmon; Creative Commons license.

Martha Nichols is editor in chief of Talking Writing.

With “Time,” Bowie was spookily prescient back in 1973. It's still wonderful and sly, music to accompany a memory journey—a journey that can be bitter, too, but that's how we continue to create, leaving our young selves behind.

You—are not a victim. You—just scream with boredom! You—are not evicting Time.