TW Interview by David Cameron

A Poet Who Makes a Place for the News

I like surgery

I like surgery

to be light. I like a cradle

overflowing with baby gifts &

stuffed-animal aliens, lime-green

to the touch. I’m really happy

for you, for your off-screen

special effects. I want you

exploding like a bridge.

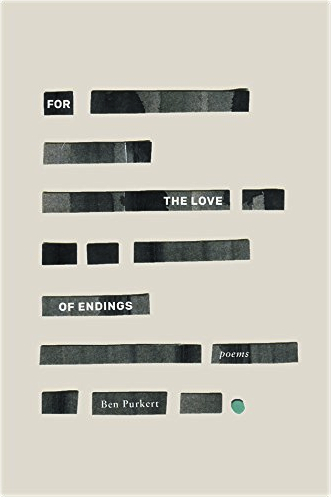

And so ends the poem “Today Is Work,” the opening piece from Ben Purkert’s masterful debut For the Love of Endings (Four Way Books, 2018). This poem, plucked from the New Yorker slush pile five years ago while Purkert was still an MFA student, exemplifies the kind of intimate, cinematic headspace that defines so much of his work: images curated from everyday life to the far-reaching shadow of consumer culture—to that final leap that pulls the rug out from under the reader.

This last effect is particularly heady, since Purkert told me he wants his poems to address not some universal “you” but the actual reader in the actual moment. “Whoever is holding the book is the beloved in some sense,” he said. That’s something every writer should consider.

Purkert introduced himself to me four years ago when our work appeared in back-to-back issues of Ploughshares. He sent me a complimentary email, and I soon became a fan. His work was unlike anything I’d read. I was struck by the way every line of every poem surprised me. At no point could I figure out where anything was heading. Imagine taking a car ride through your hometown but every turn leads down a street you never knew was there, and you can’t for the life of you figure out how so much newness can be hidden within so much familiarity. Like I said, heady.

We chatted one morning this past June in Fort Greene Park, not far from his Brooklyn home. During our discussion, Purkert quoted poet Donald Hall, and then later on, as we got up to leave, he checked his phone and learned that Hall had just died. It was one of those moments you can’t decide how much, or how little, to read into.

We chatted one morning this past June in Fort Greene Park, not far from his Brooklyn home. During our discussion, Purkert quoted poet Donald Hall, and then later on, as we got up to leave, he checked his phone and learned that Hall had just died. It was one of those moments you can’t decide how much, or how little, to read into.

Purkert grew up in South Orange, New Jersey, a place he called “pretty supportive of the arts.” He named Paul Auster, Wyclef Jean and Lauryn Hill of the Fugees, and Zach Braff as fellow South Orange residents.

We also discussed a gaggle of other poets who have influenced Purkert ever since the seventh grade. At one point, he revealed that he’d briefly been undergrad classmates with Rivers Cuomo, frontman for Weezer. Speaking poetically, I believe that too qualifies as a leap.

This TW interview has been condensed and edited.

TW: Do you remember when poetry made its claim on you?

BP: I had a teacher named Betsy Barbato in seventh grade, and she would give us Anne Sexton poems to read—

TW: Wow…to seventh graders?

BP: Yeah! I mean, like, the heavy stuff. The really dark stuff. There’s this Sexton poem [“Her Kind”] that has the line “my ribs crack where your wheels wind.” And “I have gone out, a possessed witch, haunting the black air”—I mean, it’s really dark. And so, I think I was almost turned on by that? The poetry was giving us access to this world of emotion that was sinister and brutal and honest in a way that algebra just wasn’t.

TW: I think “Sinister, Brutal, and Honest” will be the title of this interview. Who else were your mentors?

BP: Jorie Graham. She transformed my worldview of what a poet could be. I was taking her workshop as a freshman at Harvard, and this was around the time of the Iraq invasion. That was all over the news. So, I’d go to biology class and study biology, and I’d go to computer science class and study that. I went to poetry class thinking, “Now it’s time to study poetry,” but Jorie had those Abu Ghraib photos from the New York Times, all those horrible and deeply disturbing photographs, and she’d laid them out on our common roundtable. The question she posed was: How do we write poems alongside this, or in response to this, or in protest of this?

I remember thinking that’s such a testament to what poetry is and can be. Poetry is always inviting the outside world in. The message she sent, to me at least, was that poetry made a place for the news. It wasn’t the kind of class where you check what you’re reading at the door.

I’m a teacher now, too, and that’s one of the great honors of teaching, to look at what’s going on in the world and think, how can we connect to that?

TW: How does that affect your own writing?

BP: Well, there are some poets who take on the political challenges of the day more explicitly in their work. Then there are other poets who write out of a kind of political outrage, but it’s not as easy to trace their poetics to a specific political stance. My book For the Love of Endings was written largely out of a sense of despair over what we’re doing to this planet.

A poet I deeply respect, Solmaz Sharif, has said—and I’m paraphrasing a bit—stale politics makes for stale poetics. You might feel a certain way about something, and then you write the bumper-sticker version of that, but you really haven’t gone through the process of making art.

TW: A number of your poems begin with the phrase “the TV.” And Coca-Cola is referred to in different ways. Is there anything to say about that?

BP: It’s probably a function of my having worked in branding and advertising.

TW: When you were at an agency, did you like working in that field?

BP: I liked it as much as someone can like something without feeling fulfilled by it. Writing a tagline is not so different from writing a poem. You’re using an image or double entendre, you care about things like alliteration, you take a cliché and subvert it. On the other hand, you’re not making art for art’s sake. You’re serving a client. I think that’s why so many TVs pop up in my poems. I’m really fascinated and horrified by consumerism in our culture.

The only universal word we have is Coca-Cola. If you were dropped in any village or city in the world and said Coca-Cola, 99 percent of the people you meet would know what you mean. There’s no other word like that. I think it’s quite bizarre that this word is not peace or hello or love. Brands have that kind of power.

TW: How would you describe the kind of poetry you write?

BP: I’ll admit that I find it difficult to describe—or brand—my own work sometimes. Not to get off on a tangent, but often we ask writers what their work is about, and they talk about the process of its making, which is not the same thing. To talk about how something comes together is mechanical versus what is the message of this poem or this novel?

TW: Speaking of mechanics, one artist who I can listen to for hours about his process is Rivers Cuomo from the band Weezer. You familiar with him?

BP: Yes! A side note, I was in a class with him when I was an undergrad. He was an English major. We took a travel literature course together. What an interesting cat.

TW: Holy shit.

BP: Yeah. He took a bunch of years off college to tour with Weezer, and then he went back to Harvard. I was in a twelve-person class with him. I remember we read Pamela.

We had to submit close readings on the website the night before class, and I would immediately read his to see what he had posted. I remember him being incredibly attuned to when animals made an appearance in the books we were reading. He struck me as super introverted, and we were a bunch of college kids, and he was in his thirties.

TW: I definitely recommend listening to the Song Exploder podcast episode where he breaks down his creative process. It’s fascinating. But tell me about your process.

BP: I am really drawn to this idea of the “leap” in poetry. This idea that the poem heads in one direction and then jumps in another, and with that jump, you, the poet, are calibrating the distance. Because if you move too close in, you haven’t taken enough risk, but if it’s so far out that it feels arbitrary, that doesn’t work.

I love poems that ask me to stretch a bit. A poet like Heather Christle does that so beautifully. The imagination is working in such interesting ways in her poems. Jorie Graham used to say that each next line in a poem should feel both surprising and inevitable. In my own work, that’s what I’m going for. I want to keep the reader on their toes. If they know where I’m going, I feel like I really haven’t satisfied the conditions.

But it took me a while to come to this approach. I used to think that the role of the writer or artist was to have an idea and to use the page as a place to record that idea. Those poems I wrote that way, they all sucked. I don’t have good ideas!

Donald Hall has this line from an interview, “There is no poem inside the head.” For a lot of poets you need a more tactile relationship with language. It’s not just about ideas.

TW: So, how do you build your poems?

BP: I write really quickly, and I revise really slowly. Most of my poems take about a year to complete, but the first draft is usually written in about five minutes. I want to be unconscious in the work. I want to silence that voice in my head that’s insecure. For my own mental health, and for the sake of the work, I need to silence that voice. I mean, try to come up with a metaphor while at the same time you’re thinking, Does that totally cohere? I want to write really quickly so that I can’t over-think it. But then the real work begins.

TW: Can you talk about the look, the actual physical shape, of your poems? Is that something you think about?

BP: It’s a question that I’m super interested in, and it informed the book cover. I like the emphasis on the poem as a shape, and I’ve noticed that my last line tends to be short, partly because I like the tapering. Again, the book is called For the Love of Endings. I’m obsessed with endings. In my view, that’s where the poem becomes the poem, when it abandons the reader. I want it to feel abrupt. I want to leave the reader wanting something.

TW: One of the last lines that really made an impression on me is from the opening poem. “I want you/exploding like a bridge.” How did that metaphor come about?

BP: I guess from the depths of my diseased mind. I don’t really have an answer. That poem, like a number of the poems, is addressed to the reader. I really like poems that sometimes drop the façade, and the “you” really is you, the person holding the book. Whoever is holding the book is the beloved in some sense. So, how can I build a bridge with this reader I’ve never met?

TW: You’ve written essays as well.

BP: Yes, and I think the logic of an essay is very different. I wrote this one piece in Guernica last year about a phenomenon I’ve observed with my students. I’d assign a poem to them and then say, “By the way, this poet is going to come in next week and meet with you.” The students would light up. It seemed like they couldn’t believe that someone on the syllabus was actually alive. The idea of a writer as a living, breathing thing was new. I wanted to write a piece that interrogated all that.

Mary Ruefle, in her book of essays Madness, Rack, and Honey, says that a writer has nothing to teach us until they die, and once they die, they have everything to teach us. My essay attempts to wrestle with that. On the one hand, the thought is absurd, but on the other hand, there’s something that’s intuitively right about that. An Ashbery poem that’s completely nonsensical the day before he dies changes when someone shares it on Facebook the day after.

I’ve also started editing a section for Guernica called “Back Draft,” where I interview poets about their process. I do think that the question of what is a poem about is a tough one, but the question of how did the poem come into being and evolve is fascinating. Let’s look at two drafts side by side and compare them. Some poets are ruthless revisers, and some barely change anything. Revising a poem is its own kind of poetry.

For more information, visit Ben Purkert’s website.

Publishing Information

- For the Love of Endings by Ben Purkert (Four Way Books, 2018).

- “Episode 70: Weezer,” Song Exploder, April 18, 2016.

- “Flying Revision’s Flag,” Donald Hall interview with Michael Lammon, American Academy of Poets (originally published in Kestral, 1993).

- “Raising the Dead” by Ben Purkert, Guernica, September 27, 2017.

- Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Ruefle (Wave Books, 2012).