Feature by Lorraine Berry

Q: Don’t male authors get asked dumb questions, too?

A: Well…yes. And no.

Pity the female writer. Not only is she less likely to get reviewed in major magazines and short-listed for prizes, she often finds herself on the receiving end of interview questions that would leave most of us mouthing three little letters: WTF?

My frustration with author interviews came to a head last November, when Terry Gross interviewed Hilary Mantel on National Public Radio’s Fresh Air.

My frustration with author interviews came to a head last November, when Terry Gross interviewed Hilary Mantel on National Public Radio’s Fresh Air.

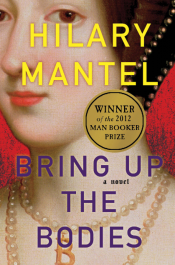

Mantel has won the Man Booker Prize twice, most recently in 2012 for Bring Up the Bodies. That novel and its predecessor Wolf Hall are the first two books in a planned trilogy about the life of Thomas Cromwell, a chief advisor to Henry VIII. Cromwell played a significant role in Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and her subsequent execution.

NPR likes to brag about its “driveway moments,” when a story is so good you sit in the driveway listening rather than going into the house. Me, I had a “drive the car into the bushes” moment while listening to the Mantel interview.

Gross began by asking about execution methods. This consumed at least a quarter of the interview, with the Fresh Air host delivering a figurative coup de grace:

GROSS: So excuse me for asking this, but if you had to be beheaded centuries ago, would you have preferred the guillotine, or the axe or sword customarily used in England?

MANTEL: Well, it’s a strange question.

GROSS: I thought so.

(LAUGHTER)

My reaction: Okay, that was weird, but now that we’ve gotten the silly questions out of the way, let’s talk about writing.

For about ten minutes, Gross did ask about the life of Thomas Cromwell—until the interview took another turn.

Mantel has suffered from health problems caused by endometriosis. In a frail voice, she explained to Gross that multiple surgeries had made it impossible for her to work for almost nine months between her two Cromwell books.

Then, in the icky moment that snapped my attention away from driving, Gross began asking Mantel increasingly intrusive questions about her body:

GROSS: So correct me if I’m wrong here. But because of the steroids that you are on to help with your condition…

MANTEL: Yeah.

GROSS: …and I think because of a thyroid condition as well, your weight just about doubled.

MANTEL: Yeah.

GROSS: And you ended up with a completely different body…

MANTEL: That’s right. Yes.

GROSS: …than the one you used to have. How did that change the sense of who you are?

Mantel soldiered on, even when Gross brought up what it must have been like under these circumstances to live in Saudi Arabia with her geologist husband:

Mantel soldiered on, even when Gross brought up what it must have been like under these circumstances to live in Saudi Arabia with her geologist husband:

GROSS: …And I’m thinking you probably already had gained the weight so you were in a new body in a country that basically granted you no rights. That must have been such a really strange and alienating period for you.

By this point, I was shouting at the radio. What did this have to do with writing? It sounded like one of Gross’s squirm-inducing chats about drug rehab with Richard Pryor or Steve Tyler. If I’d been in Mantel’s position, I would not have remained as dignified.

In Gross’s defense, this author’s struggles with weight had already been made public in a New Yorker profile; Mantel herself discusses them in her 2004 memoir Giving Up the Ghost. So, okay: If you talk about it in a memoir, you open yourself up to such questions. That’s the deal you make with the media devil.

But sometimes context is all, especially in a broadcast interview, and Gross didn’t preface her remarks with any reference to Mantel’s memoir or the New Yorker piece. Gross approached this distinguished literary author as if she were sitting next to her and had suddenly noticed that Hilary Mantel was fat.

“Could I See Your Shoe Collection?”

I knew the Gross-Mantel fiasco was not the first time I’d heard an author interview with a woman go awry. So, I did the cutting-edge thing: I used Twitter to find out if other writers, male and female, had ever experienced overly personal interview questions.

First, I sent out a general tweet, which netted me immediate responses from a number of women and one man. Then I sent a tweet to Jennifer Weiner and several other well-known female authors: “Writing article on offensive questions asked of female writers. Have you encountered this?”

Within minutes, I had my first response—from Jodi Picoult—who tweeted, “I have been asked how I lost weight. MULTIPLE TIMES.”

Weiner, who’s often bristled at being dubbed a “chick lit” writer, tweeted back, too. She also re-tweeted my query, and the avalanche began. She and I then corresponded by email, and here’s an excerpt from one of her horror stories:

In an interview for the NYT Sunday magazine that I eventually bailed out of—because the (female!) reporter’s questions were so inappropriate—I was asked if she could see my shoe collection, if I felt bad for ‘abandoning’ my husband and daughter to go on book tour, how I felt about my mother being gay, and if I wrote my blog ‘so that people would like me.’

Margaret Overton, an anesthesiologist and author of the 2012 memoir Good in a Crisis (Bloomsbury), had a similar problem with an interviewer when it came to “why” she wrote. Overton contacted me on Facebook and then emailed me this account:

My worst interviewer led with ‘So, you went through this ugly four-year divorce and wrote this book to let it all hang out there.’ He asked if I ever dumbed myself down for one of my Internet dates. I said, ‘No, I don’t ever dumb myself down. That isn’t my nature, I don’t feel the need to dumb down for any reason, ever.’ That made it pretty clear he hadn’t read the book.

He asked personal questions about my children that I would not answer, and about my ex-husband that I felt legally unable to answer….

At the end, he actually misquoted a book jacket blurb. I knew I was in trouble.

Caitlin McCarthy, a screenwriter who responded to my initial tweet and then followed up by email, remembers when an interview came with a precondition:

A reporter at a small publication that covers Irish Americans responded to my press release. He sent me an email, asking if I could give him a call so that we could set up a time and a place for the interview—so I did.

To my surprise, the reporter asked if I would drive in from Worcester to Boston (over an hour away with traffic) on a Friday night, because he had tickets to Celtic Woman. ‘Would you like to see the show with me? We could do the interview over dinner afterward.’

Uh…isn’t that a date?

When McCarthy refused, she never heard from the reporter again.

It’s not just journalists who leap out of bounds. Lauren Groff recalls readings where she was asked a number of intrusive questions:

The one that stands out was during the tour for my first book, The Monsters of Templeton, in which a main character becomes pregnant and isn’t forthcoming about who the father is. I was myself very pregnant at the time. A woman stood up in the audience and asked me if I knew who the father of my baby was.

To be sure, my survey is very informal and anecdotal. But all the women who responded to me—whether by tweet, email, or Facebook—reported that interviewers or fans had grilled them about personal details.

“Have You Ever Died?”

Of course, authors of every persuasion have grumbled for decades—if not centuries—about the havoc journalists can wreak.

Connie Willis insists that all writers get asked dumb questions. In a recent TW interview I did with her, the renowned science fiction author points out that, for the average reader (or literal-minded reporter), the idea of making up something whole-cloth out of your head is a foreign concept. They assume you must be drawing on some event that happened to you personally.

This is Willis’s generous explanation for why people have actually asked her if she’s experienced the things she’s described in her novels, including time travel and death.

When I asked J. Robert Lennon, author of literary novels like Familiar (Graywolf, 2012) and the subject of an upcoming TW interview, if he’d ever dealt with intrusive questions, he said no, not the way he knew female writers did.

But in his email response, he noted that he’d faced a different problem:

I’ve had some interviewers, always men, who frame their questions in terms of complicated and (to me) obscure references to other writers, as if to prove to me how smart they are. I’ve talked to some female writers who say this never happens to them—it’s a male pissing-contest thing.

The qualitative difference between Lauren Groff being asked about the paternity of her baby and Lennon’s pissing contest is the crux of the matter. The first question feels shaming in its intent, while the second is confrontational about the actual subject at hand: writing. In other words, personal questions directed at a male writer don’t dispute his right to be a writer. Lennon claims that interviewers have tried to challenge his intellect. But the women I heard from have been challenged in ways that implicate their bodies—through overt references to children, marriages, or attractiveness as potential dates.

“Men get insulted in a different way,” Lennon adds, “one that is less personally wounding. We don’t get asked to prove we’re legit the way women do.”

“Do You Have a Thing for Little Debbie?”

If anything, my disgust with the various ways female authors are undermined has only deepened since that “drive the car into the bushes” moment last November.

Yet, while I’ve heard plenty since Mantel’s Fresh Air interview to confirm my suspicions about female writers and bad interviews, other stories don’t fit into a knee-jerk interpretation. I’m convinced that intrusive questions are still predominantly a woman’s problem, but screaming “misogyny!” fails to get at the nuances.

In fact, the novelist who put this in perspective for me is male—Mat Johnson, recipient of a USA James Baldwin fellowship and the 2011 John Dos Passos Prize for Literature. At first, he denied getting intrusive questions. Then he asked what I meant specifically.

“Lordy,” he tweeted back. “I’ve had kid questions. Also weight questions. But as a male, there’s so much less social stigma there.” He added, “I get [questions] on race, almost always, but I’ve done work on race, so I basically consider it open for play.”

When Johnson invited me to email him, I did, asking if he saw connections between race and gender and the types of questions that writers get asked. His reply:

White, male, and straight is an invisible identity for most Americans. So when [interviewers] come up with questions, they never wonder how this very specific identity influences the work. It’s ‘the norm’…. [But] most non-white writers I know get much of the questioning filtered through identity, as if their personal identity was an artistic choice.

Yes. Just check the Paris Review, the gold standard for literary interviews, for proof that white male authors are the norm. On its interview page, 23 featured interviews are currently listed for the “2010s.” Of those 23, only 4 of the writers are women. Only 2 are authors of color: Samuel Delany and Louise Erdrich.

Racism and sexism are often linked, scuttling literary opportunities in similar ways. The connection isn’t a simple one-to-one, however. For Johnson, interview questions that seem too personal for a woman likely feel much less so to a man—“not because of personal sensitivity issues,” he says, “but because of societal expectations.”

He believes he gets asked about his weight—for example, regarding a character in his 2012 novel PYM who loves Little Debbie snack cakes—because he’s publicly discussed being a Type II diabetic. But “[a]s a man,” he writes, “it doesn’t matter as much, because I will always be more valued for my accomplishment than my appearance.”

For his part, Victor LaValle, a former National Book Award judge and author of The Devil in Silver (Spiegel & Grau, 2012), tweeted me that he encourages personal questions, arguing that “I write from my life and feel okay saying so.”

LaValle and I had a wide-ranging conversation, much of it through back-and-forth tweets. I tried to draw him out about whether he thought race played a part in the questions writers are asked, but he didn’t respond to those queries. Clearly, the impact of race—and one’s comfort level with such questions—could pack many articles beyond this one.

Still, like Johnson, LaValle did confirm that the probing questions he’s asked aren’t the same as those lobbed at women:

As a man, I do think there’s a whole range of questions/presumptuousness I never encounter…. I believe in openness, but skeevy interviewers deserve to get smacked.

“How Clueless Can You Be?”

Indeed, the skeevy among us deserve more than smacks, and maybe it was ever thus. If you’re an author in the public eye, especially an author who is not a white male, maybe it does come down to learning the right publicity tricks, to getting good at managing fools and voyeuristic creeps.

Along with many of the other women I contacted, Lauren Groff believes that female authors “have a very difficult time being taken seriously, especially early in their careers.” So, when interviewers get too personal, she says, she derails that line of questioning as fast as she can:

I’ve managed the questions in different ways, most recently by preempting the question about the alliance between my body and my work very early in the interview.

I agree with her strategy—it’s smart and survival oriented—but I’m not ready to let anyone who asks intrusive questions off the hook. The sexism and racism may be unconscious, but cluelessness, journalistic time constraints, “readers want to know,” “everyone does it”—none of that is a good excuse.

NPR’s Terry Gross is no stranger to feminism, but she couldn’t seem to help herself when she said to Mantel, “I was thinking if anyone ever needs an antidote to princess fantasies, they might want to read your books.” Mantel laughed and agreed, but then:

GROSS: Because women who were chosen as queen, that sounds really great, right, but if they don’t give birth to a male heir for Henry VIII, bam, they’re executed.

MANTEL: Well no, I don’t think it’s as simple as that, in all fairness.

GROSS: Oh, OK.

Publishing Information

“Mantel Takes up Betrayal, Beheadings in ‘Bodies,’” NPR interview with Terry Gross, Fresh Air, November 26, 2012.

“Mantel Takes up Betrayal, Beheadings in ‘Bodies,’” NPR interview with Terry Gross, Fresh Air, November 26, 2012.- “Actor/Comedian Richard Pryor,” NPR interview with Terry Gross, Fresh Air, October 27, 2000.

- “Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry,” NPR interview with Terry Gross, Fresh Air, August 24, 2004.

- “The Dead Are Real: Hilary Mantel’s Imagination,” profile by Larissa MacFarquhar, New Yorker, October 15, 2012.

- Giving Up the Ghost: A Memoir by Hilary Mantel (Picador, 2004).

- “Jodi Picoult Does Not Write Chick Lit” by Andrew Goldman, New York Times, February 8, 2013.

- “Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner Speak out on Franzen Feud: HuffPost Exclusive” by Jason Pinter, Huffington Post (books section), August 26, 2010.

- “Interviews: 2010s,” Paris Review.

Lorraine Berry is an associate editor at Talking Writing. On Twitter, you’ll find her @BerryFLW.

Just before the Mantel interview was first broadcast, she notes, a story drifted through the blogosphere about a woman writer who’d been asked, based on one of her characters, if she herself had ever had an abortion. When Lorraine contacted novelist Nichole Bernier, she, too remembered the incident, but neither of them could track down the original source.

“I feel as if my current article has just scratched the surface,” Lorraine adds. “Many great quotes from authors who contacted me ended up on the cutting-room floor, but I’ll continue writing about these issues. If you’ve got an interview story to share, please comment here or get in touch on Twitter.”