Essay by Steve Adams

Novel Writing Kicks My Butt

Near the end of Norman Mailer’s life, he told his biographer, J. Michael Lennon, that he had a novel he wanted to write. But Mailer, then in his eighties, was concerned about whether he’d finish it before dying. Novels take so much physical energy, he said.

I felt tremendous relief hearing that, as I’m hardly the dynamo, physically or otherwise, that Mailer was. The day-to-day of writing a novel, the relentlessness of it and how spent I can be after a session, has never made me feel like the most hardy of men. Novel writing kicks my butt, and yet I return again and again. For better or worse, I can’t seem to shake the long form.

I began writing fiction late, in my thirties, and by accident. After writing poetry in Austin, then moving on to playwriting in New York City, I wound up where so many writers go to die—Hollywood. Let’s just say neither the form of screenwriting nor the L.A. lifestyle was a good match for the way my imagination breathes. L.A. is where I gave up writing. Entirely. Forever. After so many years of writing and defining myself as a writer, I’d reached the end of the line.

I remember the night I came to that bitter decision as I stared at the ceiling from my futon in my crappy apartment in Mar Vista, trying to be philosophical. I’d won a few contests and experienced the almost unbearable rush of an entire audience gasping—or laughing out of control—at my work brought to life on stage. How many writers get that? How many talented, smart, distinctive writers are never heard at all? I told myself I was lucky. I’d thrown a pebble into the water—now it was time to trust in the rings moving out from it. Let it go, let it go.

After a period of mourning, I felt some relief. As an adult and a writer, I’d had nothing but day jobs—working in a health foods store in Austin and a liquor store in Manhattan and typing away on a computer in offices on both the East and West Coasts. Maybe I could find a career, even one I could in believe in a little. That didn’t seem so bad. Best of all, I could now leave Los Angeles. I decided to stay for another nine months, work hard and save up some cash, then move back to Austin.

My status as confirmed nonwriter lasted about three months. I found myself getting itchy. Agitated. I didn’t know what to do with myself, and this unease increased day by day. Finally, I sat down at the computer and told myself to write something only for me, to forget the success and money I’d chased in L.A. with the rest of the whores and fools. Just put down some words. As soon as I began typing, I felt like a horse broken loose from a plow. I ran and ran and ran, joyous in my freedom, writing prose for the very first time in my life.

That first story was an extended mess, but I didn’t care. The second was short, rich in its poetic concentration, but highly personal and not really built for publication. The third won Glimmer Train’s New Writers Award and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and anthologized twice.

It’s one of the best pieces I will ever write. I didn’t know that at the time. It seemed like the beginning I’d been waiting for, the door at last opening to all my dreams. I immediately began working on a novel, as that seemed the next logical step.

Short stories and essays are lovely things, compressed nuggets you drop into a reader’s mind, where they unfold and radiate, often with profound power. To write one that works takes a particular kind of precision. Every word must count. There are no shadows to hide in, no forgiveness. On the other hand, their brevity allows the writer to take in the whole scope and arc of a piece in a single sitting and revise accordingly.

Novels, however….

My experience writing plays and screenplays—with their emphasis on three-act structures—helped me grind through my first attempt. (I privately called it my “training wheel novel.”) I burned a bridge with one agent when I gave it to another, who promptly quit the business so she could move to Germany and marry her boyfriend. It’s just as well. The piece was at best a pretty wreck. Meanwhile, I managed to knock out a couple of short stories that got published, but no short story ideas followed.

My experience writing plays and screenplays—with their emphasis on three-act structures—helped me grind through my first attempt. (I privately called it my “training wheel novel.”) I burned a bridge with one agent when I gave it to another, who promptly quit the business so she could move to Germany and marry her boyfriend. It’s just as well. The piece was at best a pretty wreck. Meanwhile, I managed to knock out a couple of short stories that got published, but no short story ideas followed.

Hungering for a strong literary community, I moved back to New York City. I got a day job. I kept writing. One of my published short stories was begging for expansion, so I reinvented it as my second novel. It was a much more solid attempt than the first. Agents were interested in it but “didn’t know what to do with it,” and I now know it had a fatal second-act problem. I got an MFA at The New School. I started another novel.

At this point, it’d been quite a few years since I’d written a short story or gotten anything published. My ideas had become chained to the long form, a form that I was still learning. There was nothing to be done but accept it and do what I’ve always done, which is write.

One Sunday afternoon as I scribbled in a favorite bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a friend of mine, a painter, came by my table. He asked me brightly and much too loudly, “How’s the novel going?” He’d asked me the same question the week before and the week before that. “Fine,” I said reflexively, wishing I’d never told him what I was working on. But it wasn’t his fault—I was writing in public.

He went to sit at the bar, but his words kept bugging me. I couldn’t concentrate. Finally, I walked over and tapped him on the shoulder. I said, “Novel writing is like painting a mural. Except it’s five miles long. You work frame-by-frame through its length, then you have to run up and down those five miles looking at that mural, constantly making adjustments to it, because every piece of it has to work with every other piece. But here’s the problem: You can never see the whole thing at once. So when you ask, ‘How’s the novel going?’ the truth is, I don’t know. I won’t know for some time. On some level, I’ll never know.”

He looked at me as though he felt sorry for me.

I wish I’d told him what came to me later: What I will know is the experience of having written the novel, of having taken that long, hard journey day by day, scene by scene, of having paths appear unexpectedly, vistas opening, characters speaking unexpectedly and making demands. Then the whole thing collapsing—or at least, so it seems. For days, weeks, even months, you doubt the whole enterprise and yourself. You slog onward as if hacking through switchgrass with a machete, telling yourself if you just keep moving, you’ll reach a clearing. And you know what? You do.

To write a novel is an act of faith I find breathtaking. What kind of fool would attempt such a challenging and lengthy journey with its failure, from an economic perspective, much more than likely? This kind of fool, apparently.

What I’ve found? My time spent writing novels has been some of the most difficult and rewarding of my life. I’ve grown from the work, as well as from each story. The characters and landscapes and myriad crises and conflicts are as clear and as much a part of me as anything I’ve experienced in my so-called “real” life and remain as embedded as any dream or any memory.

Where your characters walk, you walk. What they see, you see. When they fail, you suffer for them, and when they earn some brief happiness or parcel of understanding, you do as well. And when you realize that through your limited but hard-earned craft you’ve somehow managed to construct a path that will carry them for a bit, one they can follow, you can acknowledge for a moment you’ve earned the title “writer.”

The truth is that the journey, the act of writing a novel, is the reward. And if you can bear the demands of the form, you will come out stronger and smarter than you were before, more sure of yourself, more astounded by and intimate with your own mysteries.

Besides, who knows? Maybe you’ll get lucky. Maybe you’ll be brilliant. Maybe you’ll catch lightning in a bottle and be able to pay your bills for a while. But even so, it’ll come back to the same thing soon enough, the day-to-day filling of the page, the black laid on white, whether it’s experienced as hacking through switchgrass, drifting slack-sailed at sea, or—on good days, and even for weeks at a time—following your characters around in wonder and horror and joy.

Publishing Information

- The Norman Mailer comment is from a January 15, 2013, email exchange between Steve Adams and Mailer’s biographer, J. Michael Lennon.

Art Information

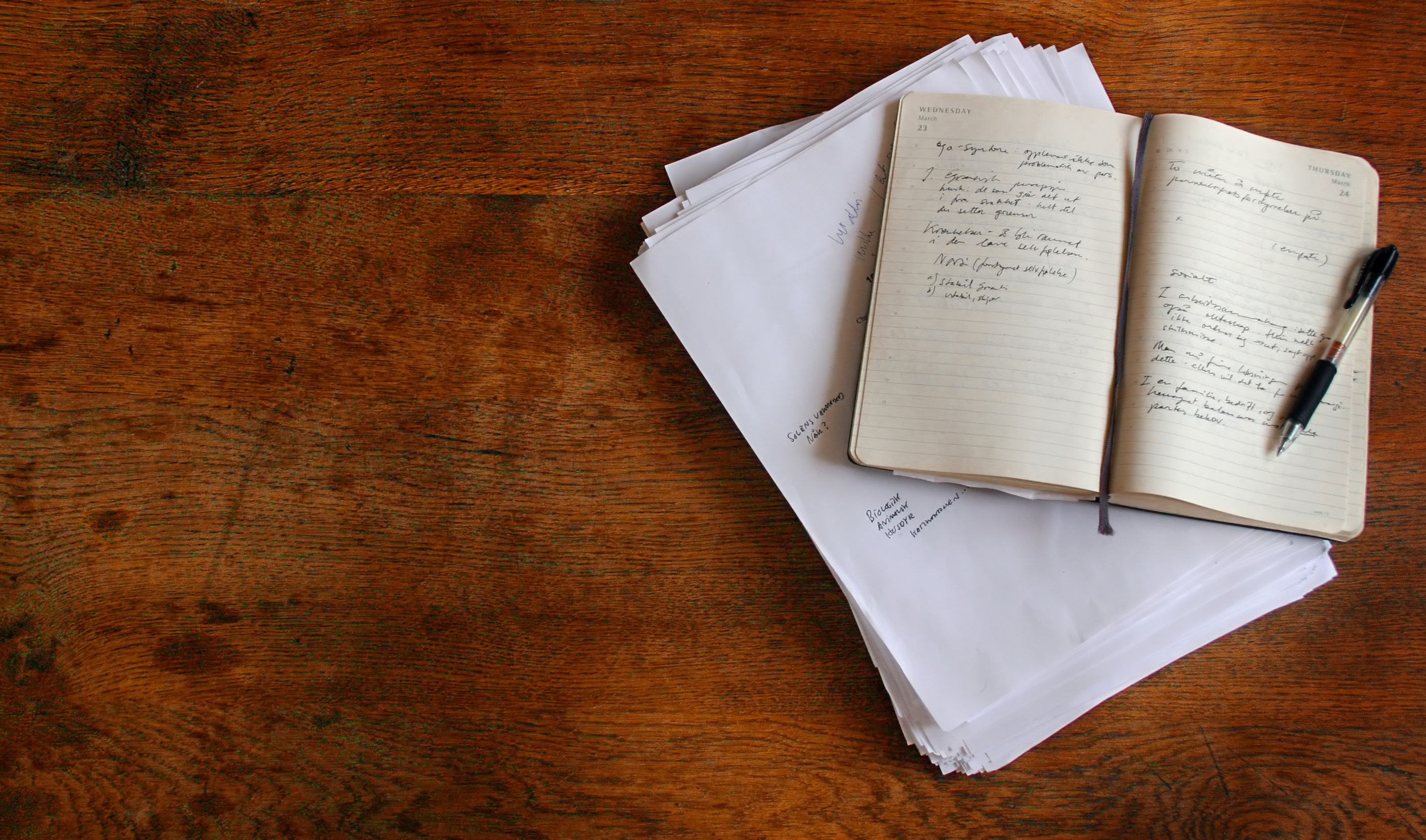

- "Novel Script on Wood" © Chris Greene; Stock Image License

- "View of Los Angeles" © Kumar Appaiah; Creative Commons License

- "New York City, Here I Come" © Rex Boggs; Creative Commons License

Steve Adams’s creative nonfiction is included in the 2014 Pushcart Prize anthology and has been published in Willow Springs, The Pinch, and elsewhere. His fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, anthologized, and published in Glimmer Train, The Missouri Review, Chicago Review, Georgetown Review, Quarterly West, and elsewhere.

Steve Adams’s creative nonfiction is included in the 2014 Pushcart Prize anthology and has been published in Willow Springs, The Pinch, and elsewhere. His fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, anthologized, and published in Glimmer Train, The Missouri Review, Chicago Review, Georgetown Review, Quarterly West, and elsewhere.

He won Glimmer Train's Short Story Award for New Writers and The Bronx Writers’ Center “Chapter One” Contest. He has been a guest artist at The University of Texas and a scholar at the Norman Mailer Writers’ Colony, and his plays have been produced in New York City and across the country.

He’s a writing coach at www.steveadamswriting.com, as well as at www.writebynight.net.