Theme Essay by Amy Hoffman

At Least One Editor Has a Database of Women Writers

AWP 2014: Amy Hoffman will be on TW's upcoming panel "Literary Politics: White Guys and Everyone Else," where she and other writers will debate why it's still so hard to break into the mainstream.

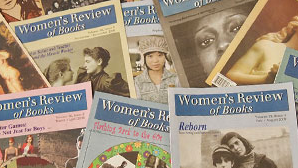

Since she wrote this commentary, the publication she edits—Women's Review of Books—passed its thirtieth anniversary in 2013. And yet, she told TW recently, the sexism she points to in this piece is as bad as ever and "very discouraging for those of us who keep pointing to the hard numbers."

In its September 11, 2011, issue, the New York Times Magazine brought together a group of pundits for a roundtable discussion, moderated by reporter Scott Malcolmson, of the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: Michael Ignatieff, James Traub, David Rieff, Paul Berman, and Ian Buruma. Scott, Michael, James, David, Paul, and Ian: not a woman—nor a person of color—in the bunch.

This particular group had been invited because each had published a significant article previously in the magazine about the issues under discussion—which doesn’t justify the choice; if anything, it makes it worse. Not only were women absent from the magazine’s special issue for the tenth anniversary of 9/11, but we weren’t included in the debates about this signal historic event in the years preceding it.

This can’t possibly be because women have nothing of interest to say on the topic. We were not only bystanders, victims, and resisters of the attacks and the wars; we were also literal foot soldiers, strategists, and architects of policy. Shortly after the 9/11 anniversary, I contacted Cynthia Enloe, a research professor at Clark University and an expert on militarism and its consequences for women, to see what she thought women would have added to the New York Times discussion. She commented:

In the immediate wake of the September 11 attacks, a group of the widows spoke out against the idea that militarized revenge was the most useful or necessary response to the killings. Women in Black, a vibrant transnational feminist peace group with branches in the U.S., seconded the widows’ analysis. Moreover, feminists in many different countries, including the U.S., quickly warned that the Bush administration was (cynically) using the oppression of Afghan women under the Taliban as a fig leaf to disguise the administration’s actual (and less altruistic!) goals.

Enloe concluded that “to ignore American women activists’ serious analyses of policy options in the wake of 9/11 and to ignore the actual consequences for women of U.S. government militarized alliances in Afghanistan is to grossly distort and simplify the politics of 9/11.”

So, what’s the deal? There’s old-fashioned, blatant sexism, of course. Several years before, a New York Times Book Review editor lamented, during a workshop I attended, that he couldn’t find women who could write knowledgeably about, say, military history. I responded that at Women’s Review of Books (WRB), we have a database of more than 1,600 women writers, with expertise on myriad topics, from armies to zeppelins, if that’s what you’re looking for.

When I can’t find someone on my existing list who would be an appropriate reviewer for a particular book, I start Googling. I’m always amazed and honored that the scholars, journalists, and intellectuals whom I contact completely out of the blue often say yes to an assignment for WRB; I can’t imagine they’d be any less receptive to a cold call from the New York Times. Yet the guys who edit magazines seem to find their writers mostly by checking out what the other guys who edit magazines are doing. The writers and ideas get passed around and around from one to the other, with only a rare break in the fence.

There’s also sexism of the internalized variety. Other editors tell me that men pitch them articles more often than women, and if their first pitch is rejected, they come right back with another idea. Women, in contrast, tend to slink away and never return. Women! Don’t take it so personally! An idea that’s rejected on Monday is often accepted on Tuesday—and there’s no knowing why. Be obnoxious, my sisters!

The organization VIDA was founded in 2009, after Publishers Weekly’s annual “ten best” list included exactly zero books by women. Since then, VIDA has published many “counts” on its website: statistical breakdowns of the number of women compared to men published by major U.S. magazines such as the New Yorker, New York Review of Books, Harper’s, and the Atlantic. Check it out. The results aren’t pretty.

Women’s Review of Books represents one kind of response to this situation: Stop complaining and do it yourself. The other path is, of course, to push your way in and change the paradigm; both are necessary. WRB was founded in 1983, and I often marvel that it’s still around. Not only because of the financial scrapes and crashes we’ve survived, not only because of the transformed publishing scene, but also because back in 1983, I would have predicted that the world would have changed enough by now that we’d no longer want or need a women’s review.

Here's what I tell male would-be reviewers: I’ll consider them for assignments if I can’t find a woman who's able to write knowledgeably on a given topic. I also warn them this never happens. There’s little overlap between WRB’s table of contents and that of mainstream publications, which means they’re not only missing out on many brilliant writers but also on important new information, ideas, and trends.

Rochelle Ruthchild, who reviewed the book Sexual Violence Against Jewish Women During the Holocaust in our own September/October 2011 issue, noted that this groundbreaking anthology, on a topic that has been taboo among scholars of the period, was greeted with a vast media silence. She ended her article with a plea: “Wake up, ‘New York Review of Boys’ and others!” (Ruthchild dedicated her review to her “Great-Aunt Anna Goldberg, who was among those sterilized during experiments by Josef Mengele and other Nazi doctors at Auschwitz.”)

When I started writing this commentary, I imagined I would have something new and deep to say about the state of publishing and the disheartening statistics for female authors. Instead, I’m making the same old points I make every time I give a presentation about WRB. But, I realize, frustrating as it is, that they bear repeating.

Suppressing women’s writing—which, make no mistake, is what our culture does—is suppressing our thought, our creativity, and even our human spirits, as the poet and novelist Eileen Myles puts it in her essay “Being Female”:

I think writing is a passion. It’s an urge as deep as life itself. It’s sex. It’s being and becoming. If you write, then writing is how you know. And when someone starts slowly removing women from the public reflection of this fact, they are saying that she doesn’t know. Or I don’t care if she thinks she knows. She is not a safe bet.

Nope, she’s not.

Publishing Information

- “The Count”—latest numbers from VIDA.

- “The Gender of Survival” (review of Sexual Violence Against Jewish Women During the Holocaust, edited by Sonja M. Hedgepeth and Rochelle G. Saidel) by Rochelle G. Ruthchild, Women’s Review of Books, September/October 2011.

- “Being Female” by Eileen Myles, The Awl, February 14, 2011.

Art Information

- Photos from "City" collection © Sarah Katharina Kayß; used by permission.

- Montage of Women's Review of Books © Wellesley Centers for Women; used by permission.

Amy Hoffman is editor-in-chief of the Women’s Review of Books (WRB). She is a member of the creative nonfiction faculty at Pine Manor College's MFA program. She's also been an editor at Gay Community News (GCN), South End Press, and the Unitarian Universalist World magazine.

Amy Hoffman is editor-in-chief of the Women’s Review of Books (WRB). She is a member of the creative nonfiction faculty at Pine Manor College's MFA program. She's also been an editor at Gay Community News (GCN), South End Press, and the Unitarian Universalist World magazine.

Hoffman’s memoir, Lies About My Family, was published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 2013. Her memoir An Army of Ex-Lovers, about Boston's Gay Community News and the lesbian and gay movement of the late 1970s, was also published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 2007. Her first book, Hospital Time, about taking care of friends with AIDS, was published by Duke University Press in 1997.

This commentary originally appeared as “Not a Safe Bet” in the Wellesley Centers for Women Research & Action Report, Fall/Winter 2011. It is © Wellesley Centers for Women and republished in Talking Writing by permission.