Introduction by Carol Dorf and Martha Nichols

TW Poetry Spotlight: Digital Poets and Nature

Computer programmers find patterns in nests of ifs and thens; statisticians in tests of significance. But poets look to the natural world for meaning—to the geometry of a leaf, wave patterns in sand, trees on a cliff. Romantics such as John Keats saw nature as an unchanging, spiritual essence compared with the messy human world:

Computer programmers find patterns in nests of ifs and thens; statisticians in tests of significance. But poets look to the natural world for meaning—to the geometry of a leaf, wave patterns in sand, trees on a cliff. Romantics such as John Keats saw nature as an unchanging, spiritual essence compared with the messy human world:

To one who has been long in city pent,

'Tis very sweet to look into the fair

And open face of heaven,—to breathe a prayer

Full in the smile of the blue firmament.

From Keats and William Wordsworth (wandering “lonely as a cloud”) to contemporary ecopoets like Gary Snyder drawn to Buddhism, many a writer has embraced long walks in the woods with no other humans to muck things up. In a well-known statement of ethics that’s appeared in a number of collections, including the 1965 anthology A Controversy of Poets, Snyder says:

As a poet I hold the most archaic values on earth. They go back to the late Paleolithic; the fertility of the soil, the magic of animals, the power-vision in solitude, the terrifying initiation and rebirth; the love and ecstasy of the dance, the common work of the tribe.

The trouble is, these “archaic values” lean on nostalgia for an era before the Internet and the internal combustion engine. For writers who prefer nature off the grid, a poem about the natural world is often written far from human habitation. It ignores rural poverty and the native people pushed out of national parks such as Yosemite to make way for a pristine idea of nature. Or it's a remnant of a past that the poem’s narrator presents as an unchangeable object. When reading such essentialist work, we sometimes wonder where the poets left their cars on their visits to the wilderness.

The ecopoetry movement can’t be reduced to Nature vs. Humanity, of course. An anthology titled Sustainable Poetry: Four American Ecopoets (University Press of Kentucky, 1999) includes work by very different writers: Snyder, Wendell Berry, W.S. Merwin, and A.R. Ammons. These days, many poets make fun of the quivering sentiment in classic nature poetry. In a 2008 tribute to Snyder from the Poetry Foundation (which awarded him the $100,000 Lilly Prize that year), Christian Wiman quipped, “Often when I hear the term nature poetry, my heart sinks a little.”

More recently, in the wonderfully wide-ranging The Ecopoetry Anthology (Trinity University Press, 2013), editors Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street bring together everyone from Emily Dickinson to T.S. Eliot to William Carlos Williams to George Oppen to Audre Lorde. “In a sense, poetry has always been ecopoetry, in that the origins of poetry are embedded in the natural world,” Street says in her introductory essay, before arguing for an eco-oriented “paradigm shift”:

But in our contemporary sense of it, ecopoetry isn’t just any poetry garnished with birds and trees…. [It’s] seeing the same things we’ve always seen, stuck on the same preoccupations, humming the same tunes off key, but with humankind as a contingent part of a much larger whole rather than the be-all and end-all of everything.

To be sure, the earth faces serious environmental challenges. Be it smokestacks or genetically modified corn, technology rarely comes off smelling like a daffodil. Yet, science and technology aren’t always the enemies of nature—and humans aren’t necessarily contingent fleas that can be flicked off Gaia’s hide. The patterns observed in nature may depend on a social or historical context. Consider the opening of William Carlos Williams’s 1923 poem “Spring and All”:

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast—a cold wind.

In a similar manner, the nine poets featured in TW’s “Nature Tech” issue focus on the techno-human world interacting with the natural world. Some even celebrate creative uses of technology. They’re a diverse group, but they share a complex passion for the environment, one that moves beyond Zen references and those lonely clouds.

In “Aged Animals in the Wild,” Pittsburgh-based Ellen McGrath Smith combines scientific phrasing and the value of information in itself—“You put it in as a search term, and bam / the information is out there”—with the realities of aging. Juxtaposing the sagging flanges of male orangutans with an old dog nosing pellets in his bowl, she nods to the way nature has entered the human realm.

So does Randall Horton in his “Echoing Narrative or the Journey Just Begun,” which plays on raccoons, deer, coyotes, and other animals returning in great numbers to the urban fringe. He creates a "brittle" mix of imagery, offering a fresh view of the urban and suburban communities where many of us live:

echoing in a sewer: a raccoon, branches.

brittle nature. fingering

the city skyline

Even poet-hermits writing on bark scraps in the wild are mediators, evoking natural glories through the abstract medium of words. We asked some of our spotlight poets about the impact of nature and technology on their work, and they all indicated the complicated role human inventiveness plays in creating art.

“I’m a city-raised Generation Xer,” Smith said in a recent email, wryly citing the limits of her “exposure to nature,” such as “fidgety moments indulging my father’s obsession with nature shows like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom.” She adds:

The digital age has only intensified the mediation of nature for me. My belated desire to be able to identify trees has led me to download the Leafsnap app on my iPad. When I have a question about natural phenomena but can’t get away to a state or national park, Google is my personal park ranger. And when I need something more intimate, I can click my way to the Hays Bald Eagle Cam, a live video feed documenting a family of eagles living near the Monongahela River, not far from the infamous Homestead Steel Strike of 1892.

Many of us now snap photos of sweeping vistas with iPhones; we’re tweeting quotes by #JohnKeats, #WilliamWordsworth, and #GarySnyder. One of the featured artists in this issue, Jess Dipierro, participated in a recent workshop called “Twice the Story: Creating Narratives with Writing and Photography in San Salvador, Bahamas” led by Horton and a colleague of his at the University of New Haven.

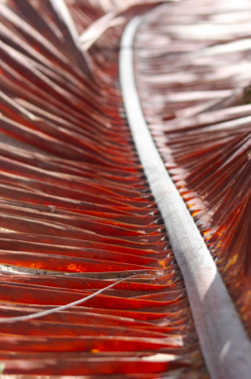

Several of Dipierro’s slides from her final project appear above and below. "I chose to place the pinwheel of palms in the center of the picture," she notes of the opening image, "because there was such a distracting background I felt it would have taken away from the original subject." As she wrote of the dramatic sea spray below:

This photo was captured while crouching down to eye level with the rocks. I waited for the perfect moment to hit the button. Finally, a wave powerful enough pushed against the rocks and produced ‘flying water.’

The effort this photographer puts into capturing a moment isn’t simply a replication of what she observes. The results are images of nature shaped by what she wants them to be. If looking for patterns feels as natural as breathing, that’s because thinking, creating, and interacting are natural to humans, too. Patterns organize thought; they allow us to communicate with one another; they give shape to chaos.

Another spotlight poet, JP Howard of New York City, emphasizes the value of virtual community, especially for writers scattered all over the globe. Of the groups of poets she connects with from around the country, Howard writes:

We exchange new poetry online daily, either via email or a private Facebook group. I love the immediacy of technology and how it can bring new poems, often by new and emerging poets, directly into my inbox. I think technology can complement poetry and make it more accessible, though there will always be a place in my heart and hand for an old-fashioned writer's journal.

For Minnesota-based Athena Kildegaard, the blessing of technology is more mixed. In her poetry, she noted in a recent email response, she’s still struggling with the all-pervasive presence of technology. ”I’m working on it,” Kildegaard writes, but it’s “baggage,” even for someone who doesn't live in a big city:

I live in rural America, in a railroad town of about 5,000 people. I can't escape the human here. Look up, and there's a satellite; listen, and there's a train; smell, and that's the whiff of manure rolling off the containment pig operation down the road. Even when I leave my cell phone inside the door, I can't get away from technology.

Of the “still life” poems featured in her TW spotlight selection, Kildegaard says they’re “a way of acknowledging the technology that's always there but almost invisible—either because we're not paying attention or we're longing for some idealized nature or we just don't want to admit we can't escape ourselves.”

For many of us, the view feels incomplete unless we see the technological and natural worlds together. In “Poem with a Line from Amy Clampitt,” which TW will publish later in the issue cycle, Meryl Natchez makes this explicit, noting that “any single, / ordinary object in the early twenty-first century / might blossom into poetry”:

The faintly grainy extruded plastic housing

of the computer,

the glow of its backlit screen,

the muffled, sibilant touch

of the serviceable QWERTY keyboard….

Natchez and the other poets in this issue join worlds: natural, virtual, wild, urban. Their work is driven by a reportorial impulse, by the joy of cataloging particular things that often animates nature poetry as well as the desire to document all that may be lost. But the urgency also originates in their understanding that life persists, even if the wildest place these poets travel is inside themselves.

TW Spring 2015 Poetry Spotlight: Digital Poets and Nature

- Ellen McGrath Smith: “Aged Animals in the Wild” and “Shaken 59”

- Athena Kildegaard: Three “Still Life” Poems

- Randall Horton: “Echoing Narrative or the Journey Just Begun”

- Carol Dorf: “Why Are You Always Writing Elegies?” and “Prismatic”

- JP Howard: “Seaside Summer” and “Haiku for the Lovers”

- Nicole Callihan: “How to Imagine a Fractal”

- Mary Cresswell: “Three Ghazals for the Dervish”

- Yvonne Estrada: “Some Will Be as Tiny as Insects” and “Sentient Bees”

- Meryl Natchez: “Poem with a Line from Amy Clampitt”

This was…taken on an off day with the sun and rain. I wanted to capture the different movements a wave goes through. I wanted the viewer to see the different stages of how a wave works—from the original roll of the wave to the crash on top of the water.

Publishing Information

- “To One Who Has Been Long in City Pent” by John Keats, originally published in his Poems (C & J. Ollier, 1817).

- “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” (also known as “The Daffodils”) by William Wordsworth, originally published in his Poems, in Two Volumes (Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme, 1807).

- Gary Snyder quote is from A Controversy of Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry, edited by Paris Leary and Robert Kelly (Anchor/Doubleday, 1965) as well as collections like Earth House Hold by Gary Snyder (New Directions, 1969).

- Christian Wiman quote from “After Nature,” a tribute to Gary Snyder (audio), Poetry Foundation, June 2, 2008.

- “The Roots of It” by Laura-Gray Street in The Ecopoetry Anthology, edited by Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street (Trinity University Press, 2013).

- “Spring and All” by William Carlos Williams, originally published in Spring and All (Contact Press, 1923).

- “Telling the Story of San Salvador Island” by Jackie Hennessey, UNH Today, February 3, 2015.

Art Information

- “Pinwheel Palm,” “Flying Water,” "Wave Movement,” and "Dead Palm" (San Salvador, Bahamas, 2015) © Jess Dipierro; used with permission.

Carol Dorf is poetry editor of Talking Writing. Her poems have appeared in Canary, About Place, Sin Fronteras, Scientific American, The Mom Egg, Spillway, Maintenant, OVS, Best of Indie Lit New England, and elsewhere.

Carol Dorf is poetry editor of Talking Writing. Her poems have appeared in Canary, About Place, Sin Fronteras, Scientific American, The Mom Egg, Spillway, Maintenant, OVS, Best of Indie Lit New England, and elsewhere.

Two of her poems are featured in TW's "Digital Poets and Nature" spotlight.

Two of her poems are featured in TW's "Digital Poets and Nature" spotlight.

• • •

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing and a contributing editor at Women’s Review of Books.