TW Column by Steven Lewis

Another Brick in the Wall

Recently, an invitation to a performance by some local kids at a “rock academy” popped up on my Facebook page. Nice, right? Admirable. Sweet, even. Except I simply couldn’t work up the mojo to go see talented children play rock and roll.

Yes, I did feel guilty about not supporting kids in their artistic endeavors. I’ll cop to feeling a bit like a tsking church lady or some shushing librarian. The tightass dad from Dead Poets Society. The other tightass dad from Footloose. It’s not like me to be such a tightass—me, the guy who wrote Zen and the Art of Fatherhood.

And yet, there is just something wrong with adults teaching kids how to be rockers. Those young wannabes should be honing their chops playing loud, clunky, off-key music in nasty garages or dingy basements where parents and other adults are not welcome. And it almost goes without saying the parents should be scowling about how it’s “nothin’ but noise!,” or banging on the door and screaming, “Tone down that racket!” (Or maybe later, voices modulated, saying, “Let me play you some Pink Floyd to show what good music really sounds like.”)

The roots of rock and roll have always been about rebellion. About confusion and hostility toward…just about everything. It’s not about pleasing your parents or grandparents or teachers or audiences who like cover bands. It’s about saying it so f-ing loud only your friends can hear you. You reach down into your sadness, loneliness, frustration, and rage—and find your own voice.

I know that scoffing at the “education” of rock and roll dates me. My kids and grandkids would say I’m just another hippie who thinks it’s all been downhill since the 1960s. But my scoffing also covers a deeper unease about teaching the arts, one that’s harder for me to acknowledge as a longtime writing instructor.

Teachers, parents, and other adults need to pause and consider the implications of shipping their uniquely brilliant /sensitive/ articulate/precocious children off to afterschool writing programs, weekend workshops, arts camps, poetry tutors et al. The path to becoming a writer—a real writer, not a Hallmark Card writer—is similar to the route of the aspiring rocker. It’s paved with loneliness, sadness, confusion, frustration, and rage. And it’s all about finding your own voice.

Teachers, parents, and other adults need to pause and consider the implications of shipping their uniquely brilliant /sensitive/ articulate/precocious children off to afterschool writing programs, weekend workshops, arts camps, poetry tutors et al. The path to becoming a writer—a real writer, not a Hallmark Card writer—is similar to the route of the aspiring rocker. It’s paved with loneliness, sadness, confusion, frustration, and rage. And it’s all about finding your own voice.

For all writers, the voice is the word. Not the story. Not the form. As Christopher Booker makes clear in The Seven Basic Plots (Continuum, 2004), there are only a few storylines in the history of literature. As the singer in Ecclesiastes crooned, there’s nothing new under the sun. And although the world is full of talented writers, the ones who touch us most deeply, the ones whose work transcends the college reading list or the New York Times Best Sellers list, are not technically the “best” or most refined writers, but those whose work gains some unfathomable, tenacious foothold in the realm of the unforgettable.

So, here’s the rub: Almost all kids—my seven and their sixteen included—do not yet have voices of their own. When they perform for others, their voices have been diverted or at least modulated through the throat of some adult. In effect, they are lip-synching their way into adulthood. It is only when they’re alone, behind closed doors and locked diaries and various hand-held devices and quadruple-folded notes to friends, that they slowly, slowly, slowly—very slowly—begin to find their singularly true, soulful voices.

Try as anyone may, no one can teach anyone else the path to the indelible voice. It is won alone. Often enough, it happens through solitude, innocence, and ignorance. Also with courage and tenacity and a powerful measure of danger and heartache, humility and humor—but always alone.

I fear that when well-meaning adults intervene too soon, those unfortunate children might never find the true voices within, each with its own unique cadence, treble, and volume. In this often counterintuitive world of writing, the greatest danger of adult intervention is not necessarily harsh criticism, which frankly never works and far too often slams the door on writing for the rest of a child’s life. No, the greater danger is praise for a voice not yet one’s own. Those kids become unwitting mouthpieces for their parents’ best wishes, teachers’ narrow aesthetics, or society’s basest intentions—mere bricks in the literary wall.

I grew up at a time when most parents and teachers, for better and worse, kept clear of kids’ inner lives, especially the inner lives of kids who sat in the back of the classroom and didn’t cause any trouble. That was me. Voiceless. A nice enough cipher who trundled off to college for no other reason than the adults told me it was a good thing to do.

My freshman roommate at the University of Wisconsin, perhaps sensing I’d scuttled my way through adolescence by anticipating what adults wanted to hear, informed me that to save my silly suburbanized soul I should write poetry. I shrugged. He was clearly an idiot. I followed my cool new friends to the Pub on State Street.

But six weeks later, clueless, dateless, depressed, confused, and six or seven beers beyond logic, I recalled his prescription for my lost soul and found a napkin, borrowed a sticky pencil from the bartender, and began to scribble a self-absorbed, whiny, pathetic, woe-is-me ode to loneliness…and bad grades.

Midway into my final hand-wringing rhymed couplet, a slinky girl dressed in black came over, put her slinky white hand on my hunched shoulder, and asked what I was doing. I instantly recognized her as one of a dozen girls with long black hair, black eyeliner, black turtleneck, black skirt, black tights, and black Pappagallos who had refused to dance—or talk—with me an hour before.

When I told her, somewhat sheepishly, that I was writing a poem, she didn’t turn away without changing expression, as she had when I’d asked her to dance. She asked what it was about.

I didn’t say it was about my deplorable social life or the D’s on all my six-week tests or my burgeoning understanding that I was not the most special Long Island Jew that Madison, Wisconsin, had ever seen. And while I hadn’t read Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, I had woken up momentarily in my 7:45 a.m. Freshman Comp class and heard someone say something about futility and the meaninglessness of life. So, I nodded and told her somberly, “The meaninglessness of life.” When her head tilted and a sympathetic smile formed on her thin lips, I added, “Futility.”

And thus I nabbed my first college date with Rhonda Something-stein from New Lincoln Prep in Manhattan.

A few nights later, rather than doing the reading for Meteorology (a five-credit class in which I was destined to get a D-minus and to tell my outraged parents, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”), I returned to the Pub, wrote another bad poem about despair, and titled it “Futility 2.” Another wan creature in black slinked over and wanted to know what I was doing: Date #2.

In the weeks that followed, I bought my first army surplus jacket, wrote more terrible poems on more used napkins, and attracted more black-clad slinky girls who seemed to like me for no other reason than I was writing poems about my utter wretchedness. After I’d shown my 22-year-old Freshman Comp TA “Futility 14,” she even did me the injustice of telling me I was a writer.

I was not a writer. I was a poser. A charming imposter, writing by the numbers, scribbling whatever some girl wanted me to say. And the following fall, I arrived back in Madison in full writer regalia: scraggly goatee, beads, enough curly flowing hair to fill most doorways, a half-dozen black T-shirts, and reams of shamelessly shameful poetry in a red rope folder.

My first stop was the Pub, where I looked around to scout out the best writing location, and, much to my horror, spotted five or six sallow boys dressed in army surplus jackets along the dark bar, a bevy of Joan Baez lookalikes at their elbows.

Instantly bereft, I found an empty corner and wrote a poorly constructed, self-absorbed, whiny, pathetic, woe-is-me poem about…not being noticed.

No one noticed.

I titled it “I Am Invisible 1.”

No one noticed. I wrote “I Am Invisible 2.”

No one noticed.

And for the first time in my life, I actually understood what it means to be alone in this universe. I didn’t speak as if I were completing someone else’s sentences. For the first time, I heard myself so that others might hear me. And while no one paid attention that evening, I knew I’d heard, however faintly, however unformed, however immature, something I’d never heard before: my voice.

Art Information

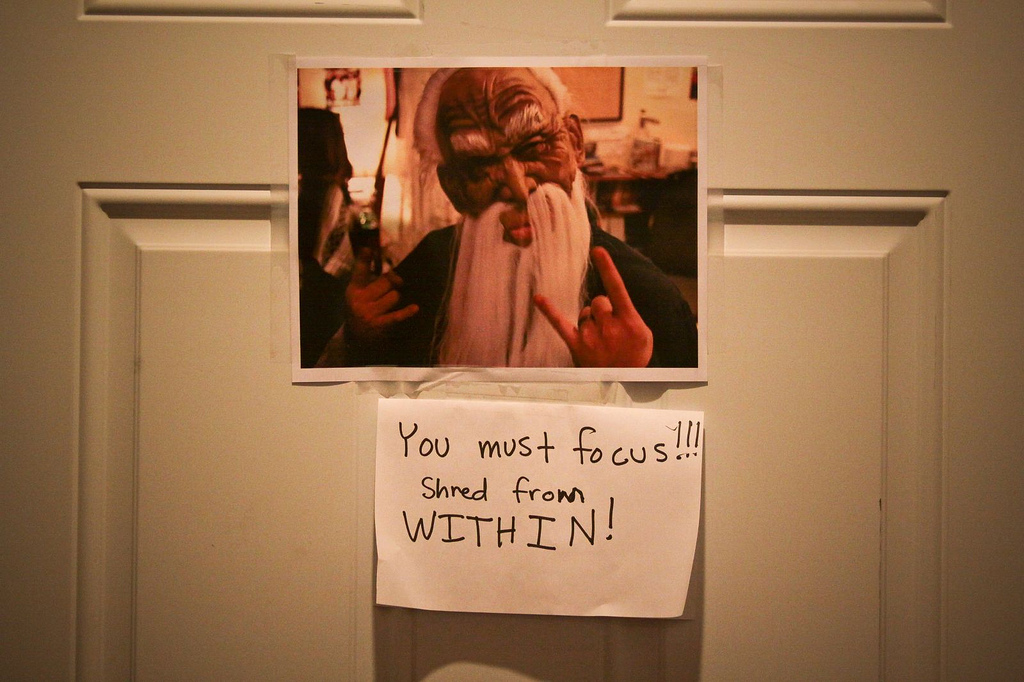

- Photos of posters, "Shred from Within!," and a couch were taken at School of Rock in Seattle, November 2008 © Bridget Christian; Creative Commons license.

- "Dutch Classroom Around 1950" © Nationaal Archief; public domain.

Steven Lewis is a contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing, a former mentor at Empire State College, current member of the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute faculty, and longtime freelancer. His work has been published widely, in journals from the notable to obscure, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Los Angeles Times, Ploughshares, Narratively, and Spirituality and Health.

Steven Lewis is a contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing, a former mentor at Empire State College, current member of the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute faculty, and longtime freelancer. His work has been published widely, in journals from the notable to obscure, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Los Angeles Times, Ploughshares, Narratively, and Spirituality and Health.

He’s also literary ombudsman for Writers Read. His recent books include Zen and the Art of Fatherhood, The ABCs of Real Family Values, The Anxious Groom, Fear and Loathing of Boca Raton, and A Month on a Barrier Island. His new novel, Take This, was recently published by Codhill Press.

Visit him online at Steven Lewis’s website or @LewisWrite4hire on Twitter.