Theme Essay by Wm. Anthony Connolly

Why Writers Need to Create Their Own Silence

It’s not a good time to be a writer. By “writer,” I mean someone who publishes with small-to-micro presses for a small audience. This kind of writer has more passion and wont than talent; this writer isn’t mainstream or popular; this writer isn’t asked to share his knowledge at a TED talk or to give readings. This writer is me.

I'd love to have more readers, but I can say without blinking an eye that I don’t write to fill some entertainment niche. I'm an artist at work, and I don’t give a monkey’s bum what anyone thinks of my chances. But I do care about how to keep writing, because doing so is tied to everything I believe as a person of faith, a cradle Catholic.

The digital world isn’t real, even if developing an online social avatar is what writers are supposed to do now to market themselves. For some, this virtual world is a mild distraction, white noise droning in the background. For me, it’s just noise, an echo chamber of hollow voices crying, “Read me, read me!” I still use social media to keep in touch with family and old friends, but I’m pulling away from all the online networking that constitutes a writer’s “platform.” I seek silence, internal silence, the kind of contemplative, solitary space that doesn’t avoid hard truths.

There was a time, a decade ago in Houston, when I felt quite spiritual—and my writing soared. I ran a good twenty miles a week. I felt a greater mystery at my core, an easiness of soul that allowed me to explore and be delighted. I would sit alone with the dusky light of the ecumenical Rothko Chapel in Houston’s Museum District, staring at the monochromatic panels Mark Rothko was commissioned to paint. I’d wander the streets using a private algorithm—walk two blocks, turn left, down one block, turn left, then right—taking photographs of whatever I came across. These were prompts: the abyss of a Rothko, the surprise of what might be around the corner. I found quiet and understanding in one of the largest cities in America.

Then my wife was promoted, we moved to Missouri, and I entered graduate school there. My faith lost some of its luster going through that most rationalist of training grounds, a humanities doctoral program. Within a few years of arriving in the Midwest, I was told I’d never run again; my back had betrayed me. While I was still recovering from surgery that fixed my spine, my 77-year-old mother died.

It’s all reading the river—once so beautiful, but when over-examined, the sheen diminishes. Personal tragedies small and large have taxed my faith in things unseen yet hoped for. Daily, I realize how insignificant I am, and this takes the air from my lungs. But it also opens the emptiness, the sacred space I need to fill back up.

After getting my degree, at my first teaching job, I met a colleague who was excitedly preparing for the debut of her first novel with a big New York publishing house. Over the course of the next year, she posted online every day: a blog entry, a photo, tweets, a link to something on Pinterest, a book trailer on YouTube, a book page on Facebook. I was impressed. Then I was appalled.

“This is what it means to be a writer today,” she said. “It’s all about the platform.”

I knew she was right, as far as publishing trends go. I began developing my own online platform, but six months in, I could see I was spending all my time writing about having written instead of actually writing. I felt as if I’d swallowed poison.

We amble about for years unaware of our dying, believing we’ll live forever—or at least I did, not in the words I said or the thoughts that preceded them, but certainly in the actions I splashed online for all to see. See what I’m doing? My book, my poem, my essay, link here, link there. As if what's not on a screen doesn't exist. A writer’s time is as finite as anyone else’s—so, what legacy will I leave? I'm a writer; shouldn’t I let others know? For too long, I thought my words could live on without me.

It's slow, our waking, to paraphrase Theodore Roethke. What kills the spirit first installs itself inaudibly, stealthily. Technology grips writers and insinuates itself in this way—a stealth installation that eats away at all we are. It’s my snake in the garden. Virtually engaged as I was, once I became more concerned about platform than plot, it was akin to believing certain deeds would shield me from death.

If only writers wrote and could let others do the shilling. If only writers could live without building an audience for the sole purpose of pickpocketing. Then such a writer, in good conscience, could write and write and write, and let others deny the fact that one day we’ll all be dead. Then what will matter is not the flotsam of social networking, but the work itself, the words on the page, the accumulating paragraphs and stories and poems and essays that come not between tweets, but because this writer has gone utterly mute, slowly increasing the effort of ink and soul.

The quiet is sweet. It is succor. I need it to hear the still small voice. I don’t begrudge anyone choosing otherwise—it’s simply not my way. I’m not building a platform anymore; there isn’t time. I’m working right now, as the great, great, great, great, great, great, great being watches over my words and doesn’t Tweet about it.

Publishing Information

- “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke from The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke (Doubleday, 1961).

Art Information

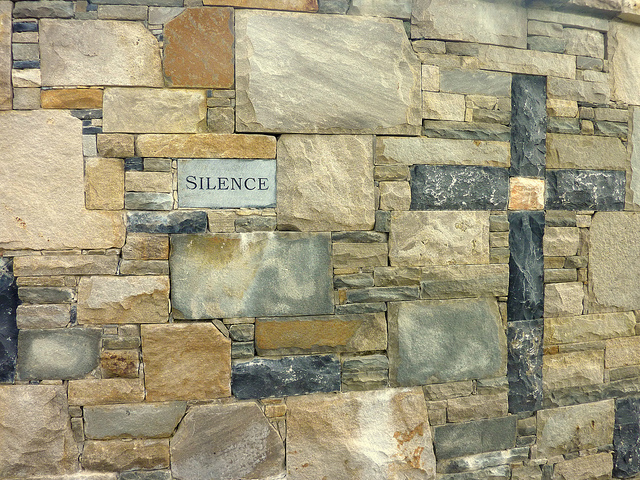

- "Silence" (Croagh Patrick shrine in County Mayo, Ireland) © Sean MacEntee; Creative Commons license.

- "The Art of Silence" (Kovalem Beach, Tamil Nadu, India) © Vinoth Chandar; Creative Commons license.

Wm. Anthony Connolly is TW’s Reading Series Editor. He’s on the faculty of the MFA in Writing program at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Missouri. His novel The Smallest Universe comes out next year whether or not he blogs about it.

Anthony notes that Van Morrison's Hymns to the Silence (1991) is one of his favorite albums. "We could dream and keep bees/And live on honey street,” as Morrison sings in “Pagan Streams.”