Theme Essay by Anjali Mitter Duva

When Your Characters Show You the Way

I was raised in France, a predominantly Catholic country, by culturally Jewish and Hindu parents. There was no religious upbringing. At home, we kvetched, and we listened to the great masters of Indian classical music. My American grandparents called me bubbeleh; my Indian one gave me comic books depicting the colorful stories of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. In my Parisian secular public school, I blended in with my French peers, except that I never smoked.

Absolved of having to commit to a single culture, I grew up comfortable with all three while still feeling like an outsider in each one. In this way, I developed a habit of observing and describing situations with some detachment, a practice that’s come in handy in my life as a writer. That detachment, however, has also presented me with challenges I never expected.

In adolescence, I watched friends and relatives go through the religious rituals of confirmation, bat mitzvahs, the tying of Hindu sacred threads. I knew I didn’t believe in any deity, and I wondered if they did, or if they were just going through the motions. I was relieved that the word “faith” didn’t apply to me.

For years, I didn’t concern myself with religion or thoughts of the sacred. But in 2001, I found myself having to think much harder about faith. At the time, I was married, working as an infrastructure planner, and living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On a whim, I tried out a class in kathak dance, a classical storytelling art form of North India. It offered the same deep connection to tradition, discipline, and structure that I’d found and enjoyed in the martial art I’d previously studied.

And as I fell under the spell of the dance—pounding out the rhythmic and mathematical patterns on the studio floor, ankle bells a-jingling, my voice singing in unison with the other students—I became friends with the teacher. Within a year, I was helping her establish a nonprofit organization dedicated to this art form. I learned about its early history as a Hindu devotional art practiced in temples by girls and women who, on the one hand, were considered vessels of the divine—and on the other, were prostituted to wealthy patrons by the temples themselves.

In a twist of fate that I couldn’t help but think was orchestrated by some unseen force, everything came together: my experience on the dance floor; my travels in northern India; my research into the history of kathak; my desire to write; my recent switch to freelance work to allow me flexibility of schedule; my affinity for planning large projects; and the arrival of our first child, which gave me a new perspective on how characters are shaped. Next thing I knew, I’d embarked on a four-book project, with the idea that each book would be set at a time of sociopolitical upheaval in India that was mirrored in the history of kathak.

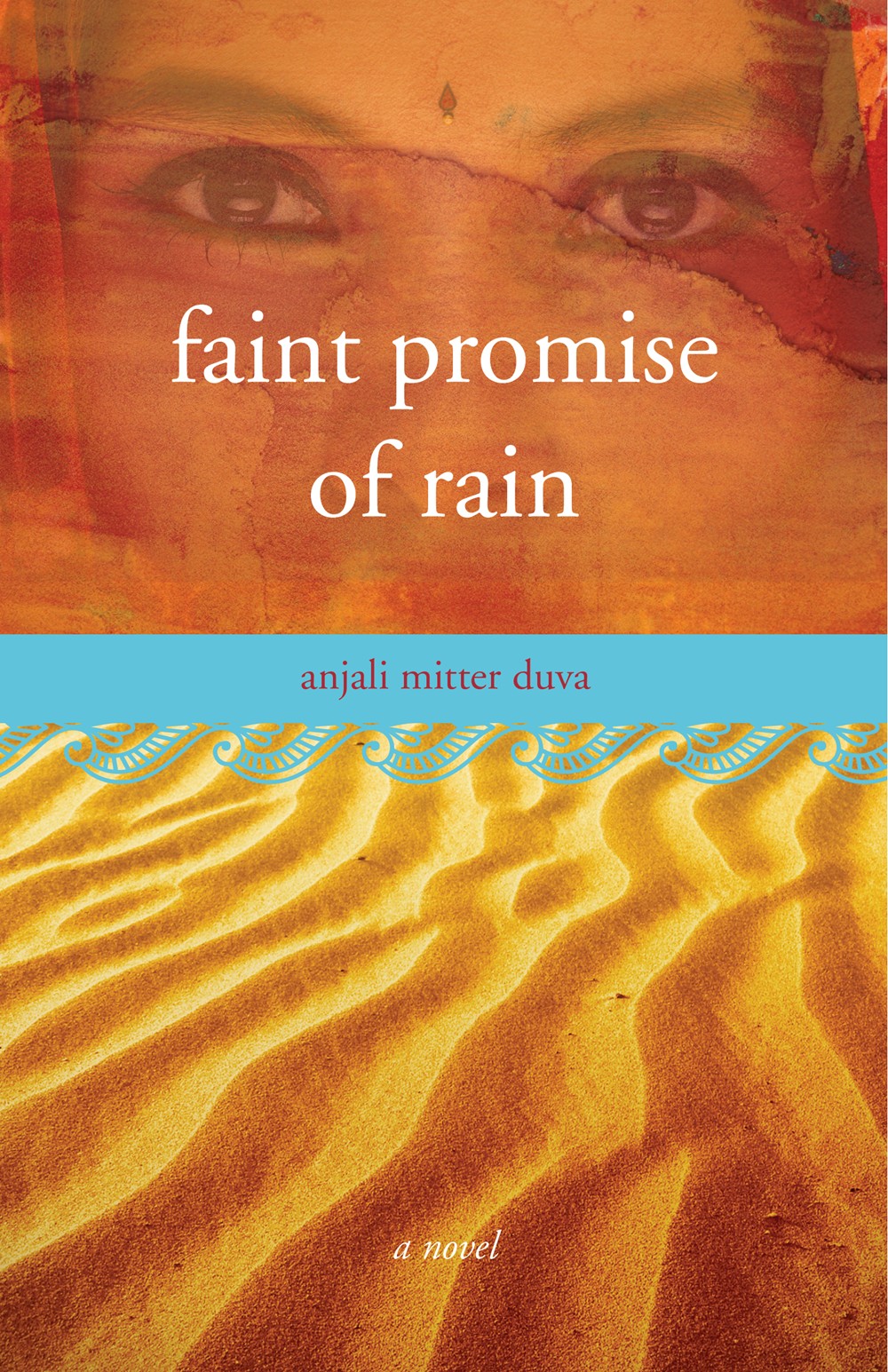

My 2014 debut novel, Faint Promise of Rain, tells the story of a young girl born into a family of Hindu temple dancers just at the start of Muslim (Mughal) rule in the sixteenth century. As I wrote this book—one whose story is full of devotional feeling and which takes place at a time of religious transition in India—I still didn’t claim any faith for myself. But I had to delve quite deeply into the faith of my characters.

Adhira, the young girl at the center of the story, uses her dance both to reach and to express the divine. Hers is the most conventional of faiths, but other characters in the book have their own faiths, each in something different. Her father, Gandar, places his in the familiarity and importance of tradition. Her mother, Girija, has faith in her children and the future. Her brother, Hari Dev, puts his faith in the certainty and predictability of numbers.

For each, their faith frames their world; it’s what they rely on for stability when they feel off kilter, for solace when they’re sad, for explanation when they’re bewildered, for hope when they’re dejected. In writing these characters—especially Adhira, my first-person narrator—I had to practice seeing the world as they did. I told myself this is what a writer does: We interpret the world as our characters would. We watch and describe from the outside and the inside, just as I’d grown up doing.

Yet, even as I created these characters, I wondered if I had the authority to portray their beliefs. I had to ask myself what my own beliefs were. What—gulp—was my own faith? I realized that to say I have no faith made me feel empty. Surely, there was something. Where do I find stability, solace, explanation, hope? The answer came, not in a blinding flash, but in a slowly expanding glimmer over a few years.

I put my faith in human connection. I believe in communication through words and action, in the openness and innocence of children and the opportunity to teach them—in the support of community and the love of family—in sheer humanity.

Despite all the ugliness that human beings inflict on each other and the planet, I place and find my faith in them. And this faith is what allows me to create characters who believe passionately in their own traditions and histories. I do, after all, have the authority to create these characters. They emerge from me, from my experience navigating among different belief systems, and from my own discoveries.

All writers write for a reason, compelled and propelled by very personal forces that allow whole new meanings to emerge from the same words. That’s part of the magic of writing. It is what writers do. We turn a mirror on the world—and whether we like it or not, whether we intend to or not, our characters turn that mirror back on us.

Here's a glimpse of kathak in action, by the guru of our school, Pandit Das:

"Pandit Chitresh Das Performs His Legendary Kathak Solo—Part 1"

Excerpt from Faint Promise of Rain

I ran all the way to the temple in the dusty grey morning. There, I slipped through the badly closed gate as the guard snored, and then sat in the courtyard, against the wall, catching my breath. Above the temple hung the type of quiet that comes only in the absence of people; the devadasis had not yet entered the temple with their sighs and yawns.

I ran all the way to the temple in the dusty grey morning. There, I slipped through the badly closed gate as the guard snored, and then sat in the courtyard, against the wall, catching my breath. Above the temple hung the type of quiet that comes only in the absence of people; the devadasis had not yet entered the temple with their sighs and yawns.

In three days, I would be one of them. Every time I thought of this, of my approaching dedication ceremony, I felt a quiver just below my ribs. Like a cocoon about to break open, I was about to take a new form. Finally, I would be able to enter the temple’s inner sanctum, to come face to face with my Lord Krishna, to perform my duties toward him. But as the day approached, my mother seemed farther and farther away, and the space between her and Bapu had widened to a deep, dark pit. Their arguments had dwindled to nothingness, and I feared, in a stomach-aching way, anything that could silence Ma.

I sat for a while longer, relishing the quiet, the knowledge that I was alone. Not even Saiprasad-ji was there. I was thankful for this, then remorseful for thinking this way. But I could not help it; something about the priest troubled me, and more so with every passing year. Thinking about him, my elation subsided. I was not ready to admit it to myself, but a part of me understood, even then, that my dealings with the priest, and perhaps with the world beyond the temple, would change once I was a full devadasi, and this gave me pause.

I stood and ran in circles around the courtyard, my arms outstretched, feeling the air rush past my arms and hands, banishing these thoughts from my mind. The flame-orange light of the rising sun slanted into the courtyard through the gateway. I held up my fingers in the shaft of light. It filtered through them and threw their long, tapering shadows onto the floor. I reached out toward a flower I could see clearly, and at first my hand was just my hand, traveling through the air. And then, the instant I picked the flower, my hand became the flower itself, and I watched my fingers opening one at a time like petals shyly greeting the new day. I felt the earth, the desert, the temple awakening through me, from the stone floor, still cold from night, to the tips of my fingers, warm with life. I stood in the long rectangle of sunlight and watched the swirling motions of my hands. They were brief spring butterflies, fluttering in the quiet of dawn. I held my fingers together, thumbs in, and turned my hands into blades to slice through the still cool air. I could make my hands into the hands of Shiva the destroyer, or Vishnu the preserver, or Brahma the creator. They could be anything.

— Chapter 8, Faint Promise of Rain by Anjali Mitter Duva

Art Information

- "Kathak: Swirl" ©Kristian Niemi; Creative Commons license.

Anjali Mitter Duva is an Indian-American writer raised in France. She is the author of Faint Promise of Rain (She Writes Press, 2014) and a cofounder of Chhandika, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the Indian classical dance form called kathak. She is a frequent speaker at libraries, schools, and cultural institutions. Educated at Brown University and MIT, she lives near Boston, where she’s working on her next book and also runs a children’s book club and the Arlington Author Salon.

Anjali Mitter Duva is an Indian-American writer raised in France. She is the author of Faint Promise of Rain (She Writes Press, 2014) and a cofounder of Chhandika, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the Indian classical dance form called kathak. She is a frequent speaker at libraries, schools, and cultural institutions. Educated at Brown University and MIT, she lives near Boston, where she’s working on her next book and also runs a children’s book club and the Arlington Author Salon.

Visit her at Anjali Duva’s website and @AnjaliMDuva on Twitter.