Essay by Lisa Solod

An Unusual—and Intimate—Look at the Late Robert B. Parker

Don’t miss “Spenser Gets the Last Word,” Martha Nichols's review of "Sixkill" by Robert B. Parker.

When Robert Parker died in January 2010, he was very, very famous. The Bob Parker I knew in the early ‘80s would have liked that very much.

In 1981, only two years had passed since Parker quit his job teaching at Northeastern and began to write full time. He had several Spenser novels under his belt but was virtually unknown outside of Boston (and not so much known in Boston, for that matter).

I was a fairly new assistant editor at Boston Magazine when a young freelance writer named Jeff Melvoin came to me with a proposal for an interview with Boston detective novelist Parker. I had never heard of him, nor had my editor, and it was a push to persuade the editor to let me assign the interview.

I read Parker’s books to date, wrote a sidebar to Jeff’s interview, and that was the beginning of a wonderful friendship.

Suddenly, too, Bob Parker’s fortunes began to change. Soon after the interview ran, Parker was being wined and dined by Hollywood elites—like Steven Spielberg.

“It was interesting,” Parker told me over lunch one day in 1981. “Spielberg told me how much he loved my work and blah blah blah. So I said to him, ‘Which scene in Wilderness did you like best?’ And he told me he hadn’t read my books; he had only read ‘treatments.’ Treatments!” Parker laughed. “I knew then just what Hollywood was really like. I decided to take the money and run.”

Parker was smart enough then and for most of the next thirty years to have a bead on what Hollywood had to offer. He admitted to liking the fuss made over him, but he didn’t take it seriously; he admitted that Tinseltown could do what it liked with his novels, as long as he was paid.

In his later years, Parker was a workhorse, churning out novel after novel in several different series. But the Spenser books came more easily to him. They remained his first love and their protagonist his most popular hero.

He wrote around 10 pages a day, which took him several hours. But he also wrote only one draft and never went back to edit—or so he said.

Many writers might disagree with that approach, but Robert Parker practically reinvented the American detective novel and nearly singlehandedly brought the series detective back from the moribund.

When I first knew him, both the writing and the fame that went with it was all rather fresh and somewhat glorious. Even as late as 1984, he loved being a celebrity. “I got out of a cab in Chicago last week,” he told me, “and some guy walked up to me and said, ‘My God, it’s Robert Parker.’ In Chicago.”

But Parker was also quick to make light of that kind of fame, mentioning his wife Joan’s aversion to it (although she would later collect consulting fees along with him). “She dislikes the fact that most people approach her just to find out what it’s like being married to Robert Parker,” he said.

The truth is that it was difficult to be married to Robert Parker. Joan asked for a separation in the early ‘80s that lasted through two years, therapy for both, and each of them dating other people before they eventually got back together. They wound up living most of the last years of their lives on separate floors of a large house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which Parker referred to in one interview as “Joan’s house and I live in it.” It was in that house that he was found dead at his desk.

• • •

For several years after we first met to discuss the Boston Magazine interview, Bob Parker and I flirted with each other over infrequent lunches. I was a young journalist who really wanted to be a novelist, he, an older and far more lettered man and a mentor.

But when I moved to Knoxville in 1981 to take a job with a publishing company, he and I began a correspondence that would span almost three years and take him from the comfort of his marriage to the separation with Joan and back again to what seemed like a sort of uneasy reconciliation with her—a reconciliation that bloomed later into a changed but perhaps stronger marriage, albeit in separate living quarters.

Despite the separation, Parker was essentially a one-woman man and, in what may be a bit of an exaggeration, said once, long ago, that he would give up his writing in a minute just to be a family man.

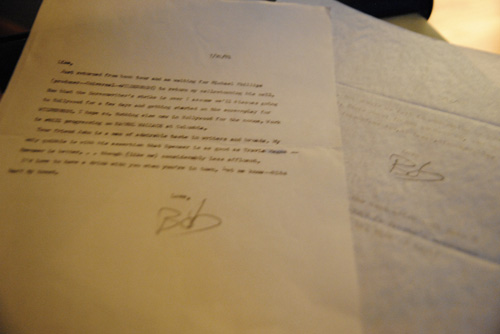

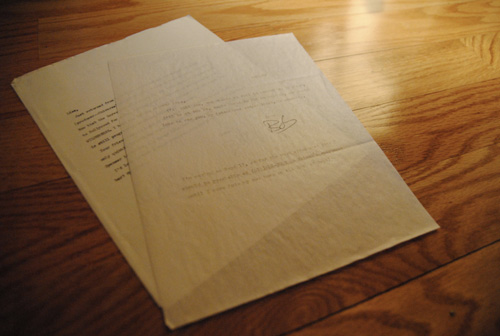

His letters to me were typewritten on a manual typewriter, some on a sort of heavy foolscap, others on what must be the first page of a carbon: tissue-thin paper now yellowing around the edges (even as late as 1984, he did not work on a word processor). “Love, Bob,” they said, although I had no illusions about, nor any desire for, love. He was smart, he was interesting, and he was successful at what I wanted to do. He was fun. And he paid attention to me.

In our first letters, I asked him questions about what he was doing and what was happening in Hollywood with the options on several of his books. At one point, he was excited that Oliver Stone was apparently writing a screenplay of Wilderness (a non-Spenser novel). Nothing came of it.

Then he saw a first draft of a screenplay of Looking for Rachel Wallace and didn’t much like it. He wished he had been asked to write the screenplay. As he dealt more and more with Hollywood, he got over that idea fast, although in a later letter he said he was writing the screenplay for Wilderness—until a writer’s strike put the kibosh on the whole thing.

He wondered what the hell I was doing in Knoxville (as did I) and a few months later, on a trip I made back north, we had lunch together. Obsessed with pesto pasta, he insisted I try it. In the twenty-first century that might not sound exotic, but thirty years ago pesto pasta was a rarity, and I first ate it with Parker at a Boston restaurant.

Sometime in early 1981, he offered to take a look at some short stories I was working on, a collection I fancied might be a novel some day. At the time, it was the most ambitious thing I’d written. Parker was very kind about what I know now was an amateurish effort at best. He marked up the stories, gave me pages of advice, and offered to send what I had to his agent.

He deemed them ready to publish but admitted that the genre was not one at which he himself was a success: His only effort had been rejected by Playboy. In his trademark self-deprecating charm, Parker speculated that it was perhaps because he had not included “enough pubic hair.”

He added that his endorsement and “$128,000 would buy a Rolls Royce Corniche. Or dinner for two at the Palace.” But his kindness in telling me I was a real writer and that my stories “were a pleasure to read” was one of the things that kept me going in the early days.

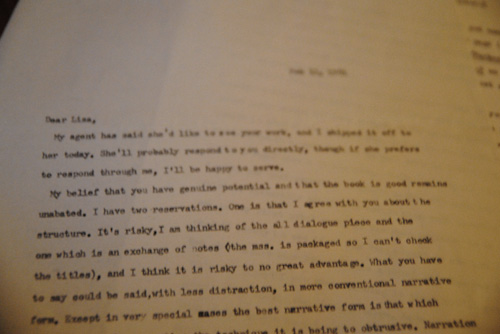

His agent was agreeable. Parker sent off my stories to her and then wrote to me with some advice about the project as a whole. His comments about character and dialogue versus narrative voice and dialogue were priceless and, if I had listened to him better back then, I might have actually saved myself some grief.

He also told me that I wasn’t to worry about what people think of my manuscript, “except people who can publish it. All other opinions are irrelevant.” He thought it was “generally a good idea not to show what you write to anyone. No one saw my first novel until it was done and ready to be mailed.” With characteristic bluntness, he added:

Then Joan read it merely to see if it was ‘all right,’ as she and I put it. She’s very smart, but she doesn’t know how to write a novel and thus has little advice to give beyond, ‘it’s all right.’ If you start showing it about, you’ll get a lot of conflicting opinions from people who, by and large, have no business offering an opinion, because few people know how to write novels (and even those who do can rarely tell someone else how).

That advice was sound and remains so. I took it to heart and have lived by it. I show my work only when I am sure it is ready to be shown, never in progress.

But Parker was more than just a mentor and sometime writing instructor. He was my friend. He was careful with my feelings and tender youth. In a reference to having been in the service, he told me that when he was my age, people had been shooting at him. He also reminded me that at my age, Chatterton was already dead. I had rather a mad crush on him.

• • •

In a letter from mid-1981, Parker was just back from a book tour and waiting for a call from Hollywood. He took umbrage that a friend of mine had said that Spenser was as good a hero as Travis Magee. “He’s better,” Parker wrote, “though (like me) considerably less affluent.”

We made plans for a drink at the Ritz Bar, his favorite, when I came to town. Once again, seeing him was fun and flirtatious, but nothing more.

Further letters detail his dealings with Hollywood and its actors and directors. At one point, it looked like Richard Dreyfus would star in Ceremony and it would be directed by Spielberg. Parker had done two drafts of the screenplay. He thought they were good. The film was never made. Eventually the Spenser novels wound up on the small screen as a television series starring the late Robert Urich. Parker didn’t like the series much at all, but he was happy to cash the checks.

In August 1982, Parker wrote me that he and Joan were separated and that they were living apart. He added that they still loved each other and did not want to get divorced but that Joan needed time. He said she was dating, as was he.

He was obviously discombobulated and readily took all the blame on himself. He called himself neurotic and credited Joan with trying to cure him of that. He said he loved her more than ever and wrote that his shrink said he was “squeezing the life out of her.” I had no doubt about that. Parker was nothing if not an exuberantly passionate man. And anything one could read into Spenser’s intense and overwhelming love for Susan Silverman applied to him and Joan.

But he also thoughtfully added that he had recently purchased a T-shirt that said “The Moose is Loose.”

Later letters got more intense. I received invitations, his itinerary; he wanted to see me, he said. At the same time, he wrote that he was “making large strides in psychotherapy”:

[T]he future for Joan and me looks optimistic. Not right away, surely, but I’d bet my life that eventually we will be together (the precise meaning of together I leave undefined until we’re a little farther along).

Parker switched gears again and said, “In the meantime I have discovered how loving and how genuinely splendid people are….yourself a lovely example.”

We met again at the St. Regis Hotel in New York in late September 1982 and slept together for the first and only time. It was lovely and strange and completely unrepeatable.

A letter the next month was naturally slightly more risqué. Although Parker remained hopeful that he and Joan would make progress toward being together, he asked to see me again. He wrote:

[A]s the second half century starts, life is difficult, complicated, eventful and exciting (though hardly painless). You are part of the excitement.

He asked me again to meet him in Nashville, where he would be touring.

I realize as I write this that I am older now than he was when we met. He married Joan the year I was born.

Late in 1982 , he wrote that he’d finally settled into a house. The rest of the letter was news about his work, asking me about jobs I was seeking, and a note of advice again: “Every important job that I tried for fell through until I was 42 (and published Godwulf).”

Late in 1982 , he wrote that he’d finally settled into a house. The rest of the letter was news about his work, asking me about jobs I was seeking, and a note of advice again: “Every important job that I tried for fell through until I was 42 (and published Godwulf).”

A month later, he sent another plea to meet him in Nashville.

I didn’t go. I felt on unsure footing about seeing him again, and I knew full well that I was just a small indiscretion in the hesitation of his marriage.

• • •

The last letters I have from Parker were written early in 1983. He reminded me about our drinks at the Sheraton Russell and told me to see The Verdict, which was filmed there. And he said he wanted to see me: When was I coming up?

But he wrote much, too, about Joan and her own search for answers, how she was now in therapy herself and “detaching herself from the man she had been seeing.” Parker said she needed to learn to live without being so dependent on him and that they were working on this, seeing each other fondly but casually.

Parker, as much as he protested, as much as he participated in his own therapy, was clearly uncomfortable with that. He was as macho as he seemed, as alpha as his first hero Spenser. He was a traditionalist. He had found the woman he loved, and he wanted to be with her forever. Everything else, no matter how fun or how interesting or how much he might desire it at the moment, paled beside his desire that he and Joan get back together and stay that way.

In more than one interview, Parker was asked about Spenser’s long and loving relationship with Susan Silverman and why he made it such a linchpin of the series. His standard answer: “Given that such a relationship is the linchpin of my life, I probably had little choice.” That was the Bob Parker I knew.

His last letter, written as I was planning to return to Boston, job or no job, was light and friendly and sweet—like the very first letters we had exchanged. I remember seeing him a few times for lunch and drinks, but there was never anything more between us except for his generously agreeing to be interviewed by me for a 1984 article in the Boston Herald.

In that long piece, he was incredibly honest and forthcoming. I wrote that he was “an ordinary man who just happens to have gone from relative obscurity to nationwide fame and considerable fortune in just under a decade,” adding that his “ego is as large as his bulk.”

I like to remember those days, when Parker was hovering on the edge of superstardom (for a writer). Though we remained friends for another year, when I married and left Boston for good, I never saw him again. My mother ran into him at a book signing, and when he saw her name, he asked if we were related. When she said I was her daughter, he told her how fond he was of me and asked to be remembered when next we spoke.

The dozens and dozens of tributes that appeared after his death testify that readers (and even the writers he befriended) see what they want to see in an author like Parker, although as far as I knew, in his case what they saw was pretty much what he was. His Spenser, a “knight errant” as more than one critic dubbed him, had a lot of Parker in him: strong, macho but not obnoxious, old-fashioned, but a serious defender of the underdog and basically an all-around nice guy.

It was Parker’s generosity with other writers, his willingness to be interviewed even as he was usually asked the same questions over and over, and his childlike wonder at how famous he had become that made people like him and want to be around him. He might have been neither perfectly happy nor perfectly successful, but he sure appeared that way most of the time. He was a hell of a wordsmith. That’s not a bad epitaph.

Robert B. Parker’s posthumous novel Sixkill was published in May and immediately climbed onto the bestseller lists.

A Robert B. Parker Sampler

- The Godwulf Manuscript, originally published by Dell, 1973 (first in Spenser series).

- Promised Land, Putnam, originally published by Dell, 1976 (Spenser #4; winner of Edgar Award, 1977).

- Wilderness, originally published by Dell, 1979.

- Looking for Rachel Wallace, originally published by Dell, 1980 (Spenser #6).

- Night Passage, Putnam, 1997 (first in the Jesse Stone series).

- Family Honor, Putnam, 1999 (first in the series about female detective Sunny Randall).

- Sixkill, Putnam, 2011 (last in Spenser series, published posthumously).

Art Information

- Portrait of Robert B. Parker © David Howells; used by permission

- Images of letters from Robert B. Parker are used courtesy of Lisa Solod

A fiction and nonfiction writer, Lisa Solod has published dozens of short stories and essays in magazines, newspapers, anthologies, and online. Her 2007 book Desire: Women Write About Wanting was published by Seal Press.

She has just completed a novel entitled Shivah. Lisa is also working on a memoir called A Change Of Life: Confessions of a Middle-Aged Feminist and blogs at MiddleAgedFeminist.com. Of her summertime plans, Lisa says: "What I am doing for the summer break is what I do all year: write. ☺"