Book Excerpt by William Least Heat-Moon

Chapter Six of Writing Blue Highways

Editor’s Note: In the late 1970s, William Trogdon took a cross-country trek through small towns in a van he dubbed “Ghost Dancing.” His marriage had just broken up; he'd lost a part-time teaching position in Columbia, Missouri; and, as a recent Ph.D., he couldn't find another job. His experiences on those back roads, talking and photographing the people he met, became the bestselling book Blue Highways: A Journey into America, originally published in December 1982 under his non de plume William Least Heat-Moon.

Blue Highways didn’t come easily, however. Decades later, Least Heat-Moon has written Writing Blue Highways: The Story of How a Book Happened (University of Missouri Press, 2014). TW is delighted to reprint a chapter here as part of our Reading Series. It took Least Heat-Moon four years to turn that three-month journey into the iconic Blue Highways, years in which he worked a day job as a probate-office clerk in the Boone County Courthouse.

The excerpt that follows comes at just about the halfway point in Writing Blue Highways, when he considered giving up. It's a nod to the value of editors (the late Jack LaZebnik, to whom the book is dedicated) and the trials of those who live with writers (the author’s partner, the pseudonymous Lucy). TW readers will recognize it all: rejections, despair, bloody Marys.

To read more of this rich combo of memoir and writing advice, go to the University of Missouri Press page for Writing Blue Highways.

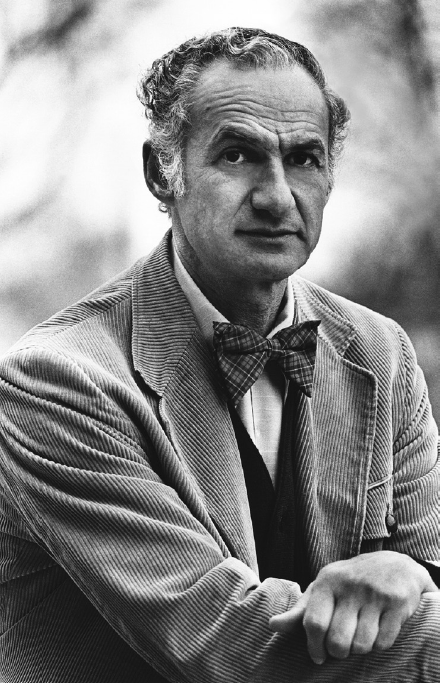

On weekday evenings in December, I began revising the opening pages in hopes of seeing what a finished text might look like, something good enough to show my longtime friend Jack LaZebnik, a playwright and poet and a skilled portraitist who covered his office walls with mural-size drawings of Twain and Faulkner and Hemingway. As he had for several years, Jack was working on a novel, rewriting, rewriting, rewriting something that would never be published. He was sixteen years my senior, a World War II pilot of a B-24, the Liberator, who had feared the war would end before he could get in on it, but his Jewish ancestry gave no special meaning to his bombing runs against Nazi positions in northern Italy and southern Germany. He just loved to fly. To him flak was little more than hail on the roof of an automobile.

He considered those missions a greater contribution than four decades of teaching English to college students; he would say, “I go into class hopeful and come out hopeless.” His Russian-immigrant father ran a junkyard (the university-educated son thought scrap yard too refined a term) in Jackson, Michigan, and Jack became a junkyard dog guarding the English language: Nobody’s solecism escaped his correction—waiters, clerks, friends, children, wife, professors, columnists, the New Yorker, and (twice) surgeons ready to operate on him.

Fascinated by Abraham Lincoln and of equal height and angularity, Jack was himself Lincolnesque, and his best plays are Lincoln and Mary and John Brown. His last work, a lively production, was about his parents immigrating to America.

From his hundreds of poems, virtually all of them unpublished, here is “The Folding Time”:

In those days Ma boiled the sheets

in a copper tub on the blue-gas stove,

then wrung them damp and hung them long

on the white lines across the back yard.

And then the folding time: she at one end,

I at the other. We folded once and pulled

and snapped the sheet to wave a flow

from her to me to her and walked together

to meet at the middle to take the ends

and I to bow at the bottom side

and back again we pulled

to stretch the cloth and snap

like a loud wet kiss to make the wave

burst to our laughter in the ritual dance

until the surprise of the calm when we touched

fingers at the warm white folds

upon her uplifted hands.

Jack was dedicated fixedly to Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, a classic guide he did not interpret but obeyed as Moses (in whom he believed) did God (in whom he didn’t). Over the years we often debated issues such as whether a pair of concise, independent clauses had to be separated by a period or could get by with a comma (he arguing for the former, I the latter). Despite our sometimes discrepant views, to me his judgment of good writing was supreme.

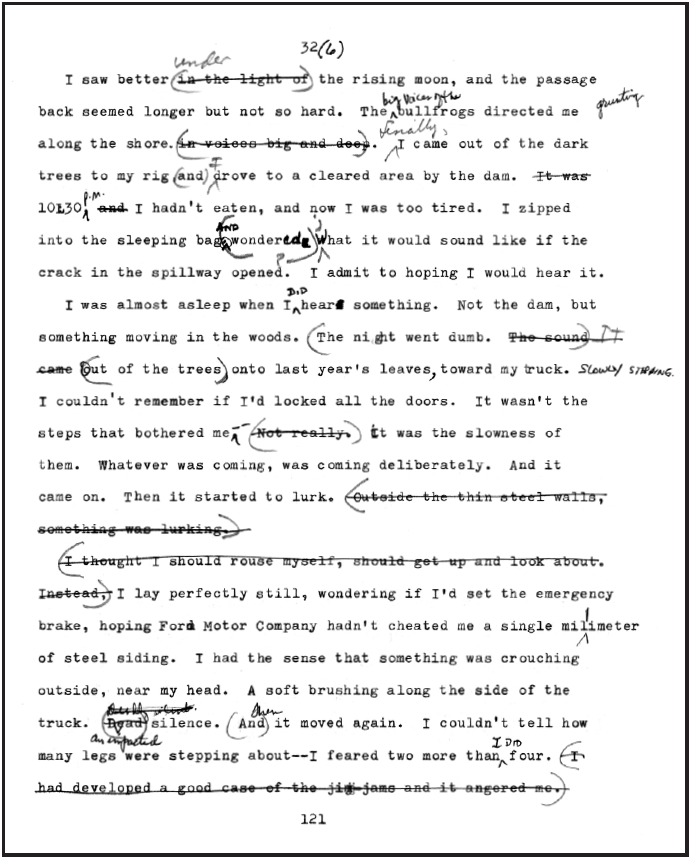

In his editing of my work, Jack never disparaged and never marked a weakness without suggesting a solution. He was unlike a later publisher’s editor whose entire comment on eleven pages of PrairyErth was, “This chapter is rickety.” Always looking for distinctive expression, Jack’s goal was to improve a sentence without imposing on it his own voice. He worked to draw a better phrase out of a weak one, and his primary tool was a pair of penciled parentheses wrapped around a word, a clause, a sentence, and occasionally an entire paragraph. In his hands my manuscript line “I saw better in the light of the rising moon” became “I saw better under the rising moon.” He was a master snipper and clipper, and his parentheses looked like little scissors, appropriately so because in Czech the word for “barber” is lazebnik.

Our shared love of language used correctly, evocatively, and boldly led us to concoct “the test,” also called Name the Fame Game. One of us would read aloud the opening paragraph of a novel and then a paragraph or two further in, usually avoiding dialogue; the listener was to appraise the language and guess not author or title but the reputation of the work. Rarely was Jack’s opinion amiss, although one book left him undecided: “The writing’s superb, then it stumbles, then it’s surprising.” The novel was D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers.

On another occasion I read him this passage (play the game and judge for yourself before you read his verdict and learn the title):

It was beautiful in Longmont. Under a tremendous old tree was a bed of green lawn-grass belonging to a gas station. I asked the attendant if I could sleep there, and he said sure; so I stretched out a wool shirt, laid my face flat on it with an elbow out, and with one eye cocked at the snowy Rockies in the hot sun for just a moment, I fell asleep for two delicious hours, the only discomfort being an occasional Colorado ant. And here I am in Colorado! I kept thinking gleefully. Damn! damn! damn! I’m making it!

He said, “Nothing there to get your teeth into.” Good writing to him was like a good sirloin, something chewable and best consumed slowly. I held up the cover of On the Road. He said, “I rest my case.”

Trusting no one else to keep his obituary free of passive voices and split infinitives and common tautologies (blinked eyes, shrugged shoulders: “What else can you blink or shrug?”), he wrote his own obituary two years before he died:

Jack dreamed of being a writer more than putting himself seriously to writing yet he continued to write disappearing poetry, plays, and novels. The thought of not existing frightened him at one time, but in the final months he found he was not afraid, and he said he wanted all his family and friends to dream of him—but no nightmares. May his name come up like a smile, an old joke, a faded picture, and that too pass away.

Because he gave his body to the medical school of the University of Missouri, he has no tombstone, but if he had, he once told me he’d want a single-word epitaph: ALMOST.

On New Year’s Day of 1979 I reached page 270 of the first draft of Blue Highways and shifted to revising recent pages. (In going from pencil to typewriter, I edited as I went, but I counted the two versions as only a single draft.) A week later I carried them to Jack for him to see, the first reading other than by me. I awaited his appraisal with considerable expectation and a belief completion was in sight.

He phoned the next evening and invited me to his home. Because of its age and his lackadaisical maintenance, he called it a “shack” (his skilled repair of sentences and paragraphs didn’t extend to broken steps and loose hinges). While I looked over his shoulder for two hours, he went one by one through hundreds of words and passages he’d marked, making suggestion after suggestion, sometimes returning to a phrase to comment further, but withholding any overall judgment, the key response I wanted. “Here’s another passive voice,” he would say, or “You’ve already told us this,” or “Don’t gild the lily,” or “Careful! You don’t want to knife this man,” or “A semicolon here would be elegant.” He loved semicolons and liked to quote Lincoln’s judgment of the punctuation mark as “a very useful little chap.”

I’d written the manuscript entirely in the present tense, a common approach, he believed, of novice writers. “If you keep it, maybe you can find a publisher,” undercutting his sentence with a head tilt meaning, “Don’t count on it.” Looking to ease the criticism, he said, “The French love the present tense—but you’re not French.”

He kept turning pages, slowly, so slowly. Once he said, “I didn’t know this word, but I think you can keep it because you should trust a reader’s intelligence even though you know you’ll lose those who don’t really care. But it’s fatal to write down to what you might perceive as someone else’s capacity.”

As we neared the third hour of the critique of only a handful of pages, I was still waiting for something unreservedly positive, an unqualified anything. At last I pressed him to assess the overall merit as if we were playing Name the Fame Game. He dodged judgment three times until I reminded him I’d been in the Navy and could handle blunt words, but still he talked around appraisal. To vex him into a response I resorted to bebop: Just lay it on me, dad. That worked. He scowled at the lingo, and said softly, “I’m disappointed.”

Former sailor-boy or not, I found those two words blunter than I was prepared for. Jack was, after my father, the most respected and influential male in my life, and for me to disappoint him was to embarrass myself. As I walked home in the January night, a folder of typed scrap under my arm, I remembered a line from an old fellow I’d met when the blue-road journey passed through Shasta County, California; only a couple of days earlier I’d written about him and quoted his frequent phrase at an annoyance or a negative outcome, words frequently in response to directions from his imperious wife: “Well, boys, there you have it.”

Deflated, reduced, emptied, I’d done nothing more than turn a half year of my life into pages good for nothing other than engendering futility. The goose eggs had proved infertile—or maybe the metaphor should be something about the stillborn. What’s the broker’s adage? “Cut your losses short”? That grew into self-justifying clichés: At least I tried. I gave it everything. Nothing ventured, nothing—Dah-dah-dah, yada, yada, maunder, maunder. The hell with it all. I could live with it.

But I couldn’t. The next morning I faced the inescapable: Without the so-called book project, what was I going to do? How does one get up from what feels like a coup de grâce? How do you tell people you’ve quit? How do you tell yourself you aren’t capable enough?

That dismal afternoon, in a campus bookstore, Lucy and I were scanning a long rack of pulpy novels, but no matter their worth, they were published books. Trying to lift my spirits, she said, “When you see all the junk that comes out, that’s got to give you encouragement.”

• • •

A well-known American author once advised writers to write as if they were dying. How could it be otherwise? (Those among us not on the road to the tomb, give a signal so we may learn your secret.) If her meaning is to write as if it’s your last book, then I concur, but if the intent is to write as if you have only weeks to live, then I find the counsel useless; what would be the point? I was writing then—as now—to live, and when the time comes, should my death come with notice, I think my response will be to put down the pencils, shut off the laptop, and watch Buster Keaton movies.

Along with such questions of mortality, I put my revising aside—and less successfully, my doubts—and gave another go at continuing the first draft. My mother had said I needed a visit from Mister Will Power and his bulldogs Pluck and Spunk.

In near disbelief, I found myself picking up a rhythm again, and two weeks later I reached page 300, what seemed a milestone figure. Ten days afterward, another twenty-five pages, and four days beyond that, in a single day, I turned out eight pages about a slough of despond in the back-country journey—miles I’d been dreading to describe—the crossing of North Dakota and, as it proved, the three-quarters mark of the trip. By forcing relentlessness, I managed to steam along although oblivious to ways the requirements of the courthouse and the inexorable weekend sessions were draining, if not warping, me.

Before falling asleep each night, I read only books written with styles I admired, paying little attention to story lines and instead studying structures and sentences possessed of uncommon mastery; my hope was superior expression would percolate into the half dreams of early sleep. The reading often kept me going late despite the certainty of the early alarm. Even after I forced myself to turn off the lamp and began drifting into that demi-world before deeper sleep, phrasings I’d struggled with during the day sometimes arose transformed. I would wearily turn on the lamp to jot down the improvements. On a productive if exhausting night, the changes would bubble up four or five times, always just as I was dropping off into moments when a peculiarly fertile semiconsciousness can open a new closet of the mind. The subconscious does its best work on things the conscious brain has been hammering away at. At breakfast, my tired head would droop toward the cereal bowl, and once I awoke when my nose dipped into the cold milk. But those reborn phrases, almost to the last one, survived to appear in Blue Highways, including “It was the night before leaving” turning into “Beware thoughts that come in the night.”

Each weekend morning, just before taking up pencil or the typewriter, in hopes of purging the clumsy sentence rhythms of my daily speech, and fostering improved euphonies, I would reread certain eloquent passages in books I kept at hand. Among them were Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa with its beautiful opening paragraphs, Eleanor Clark’s The Oysters of Locmariaquer, James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Melville’s “The Encantadas,” Faulkner’s “The Bear,” and always my compact Shakespeare. Throughout the week, I was careful about what I read, perpetually trying to stay with only accomplished expression: happening upon an inept paragraph could throw echoes requiring an hour of good readings to silence.

• • •

On a Sunday in late February, at the end of eight hours of writing, something happened. I don’t know what triggered it, but I found myself, as if abruptly awakened, standing above the typewriter, a sandal in hand, beating the devil out of Mount Olympus. (The idiom here may be more literal than figurative.)

Lucy, not yet exposed to the madness that attends writing, watched from the sofa. She was frightened nearly to tears. She said almost inaudibly, “Oh no! Oh god!” I was insensible to what a chore book writing can be for those not doing the writing, especially those not permitted to read any part of it. The question of inclusion is tricky for a writer, and denial of it is dangerous to everybody near, so it should be answered cautiously, wisely, with a generous eye toward some sort of sharing greater than just the burden.

I sat, put my head down on the Olympia. After a spell I whispered, This goddamn would-be book is making me insane. After a few uncertain minutes, Lucy asked, “Do you think you can handle a bloody Mary?” It was the one thing I could handle. We talked. Well, I talked. Fast, nonstop, madly. I told her that as much as some self-described “book” meant to me, my sanity meant more. There I paused, and then the gates came unhinged: I’m through, I’m quitting, have to quit, what else can a man do, they’re not putting me in a straitjacket, there’s gotta be a way, I’ve been fooling myself, when a guy doesn’t have it, what the hell man, things are turning noxious, maybe they can stop the book but they’re not going to drive me off my nut, nogoddamnsiree! Ramble, ramble, ramble. And I took a swallow of what seemed more my blood than Mary’s.

I have all of this from Lucy’s report the next evening—just before, in her nervousness, she spilled a glass of ginger ale onto the typewriter and the syrupy stuff stuck the keys together and locked the machine down. I think it was an accident, despite being a strangely appropriate happenstance a religious person might see as divine intervention, or a psychiatrist view as the act of someone subconsciously trying to protect something.

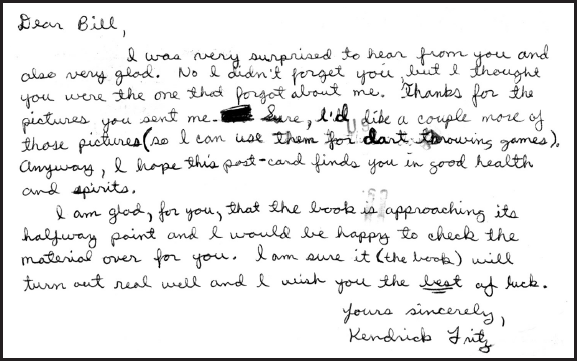

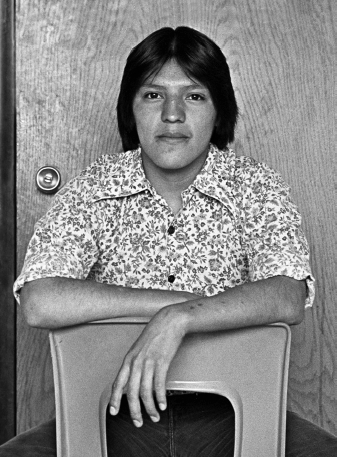

During the time a repair shop needed to free the keys, I kept thinking (again) about the necessity of maintaining an established rhythm, so I returned to revising—not so much rewriting as tinkering with fouled and unfit words refusing to release their chokehold. For escape, I got in touch with the people I’d photographed to remind myself they were real and not phantoms from a dream of a journey I’d never made. Their responses were life rings tossed to a tired swimmer still far from shore.

On the nineteenth of March, one year from the night before the journey began, I took a new revision to Jack who forty-eight hours later phoned to say he had just read several encouraging paragraphs. “You do your best in writing about nature.” But the book is about people! “I know.”

Well, boys, there you have it.

• • •

Lucy called a cousin who worked in New York City as a publicist for Doubleday and persuaded her to persuade an editor to look at some sample pages. With the typewriter out of commission, Lucy suggested getting away during her school spring vacation. I was uneasy about a nine-day hiatus. She said, “You’re giving more of your life to that book than to us.” That book right now is my life. “So why should it have to be mine?”

Four days later we took off eastward in Ghost Dancing to escape the dislocations in the little world I’d created for us, but along the way she was willing for me to check some facts of my reporting. Even though now shared with a companion, the back roads gave their quietude, and they rekindled in me a clarity of mind as they strengthened resolve. When we returned, I sent the Doubleday editor a sampler of twenty-five pages with three photographs.

He was fast. On Shakespeare’s birthday I received my first rejection: “Perhaps your travels seem interesting to you, but to others...” So on and so forth. I thought, Every time a guy gets a little footing, there goes the rug from under him. I had to reset my assumption about how far I was from achieving the book I imagined, and even then the distance was to be years beyond that recalculation.

Doubts pushed me into drawing up a list, “Eleven Thoughts on Rejection Dejection,” responses to questions one side of me was asking the other. I admit the weary voice of continuance half hoped retreat would prevail:

- A real writer perseveres—he cannot do otherwise.

- The only effective escape lies in more writing.

- Cease evaluating and just write.

- If first you don’t succeed, write, write again.

- Better to fail than walk away haunted.

- How much do you respect failure?

- What else is really worth doing that you could do?

- Write until you prove unequivocally that you can’t.

- Try quitting to see how you like it.

- Write your best today and the hell with tomorrow.

- To keep writing is to live in hope and possibility.

• • •

Somebody, wanting to help, alerted the Columbia Daily Tribune about “a man who works in a metal box in the courthouse and is writing a book about running away.” My desk had been moved from the front door of the probate office and into the steel vault holding the last wills and testaments of Boone County, Missouri. It was there that the previous probate judge shot himself to death—why, nobody could tell me. Maybe he was trying to write a book. Any suspicious brown spot on a file or deed, I construed to be his blood. Here was an affiant saying naught but suggesting much.

It was that metal suicide-box, as best I can determine, that caught the attention of reporter Jim Herweg. Should his interest lead to an actual news story, I figured any urge to quit would be further challenged: Half the town would know I’d given up (and, to be truthful, there were a few ready to gloat). Beyond all that—who could say?—maybe somewhere a book editor would come across Herweg’s story and ask to see what I had.

One afternoon he came by the apartment for an interview. Several times he referred to the manuscript as a “travelogue” until I stopped him to say that while what I was writing grew from a travel log, the finished work would not be a travelogue. Check a good dictionary. (Even today, I correct that noisome term.)

What Jim Herweg wrote became the first published words about Blue Highways. The feature story, to my surprise, led my family to see it as an indication “this book thing” might be something more than just another of my escapades without real purpose or longevity, and their silence about my writing, for a while, lifted.

No matter the lets and hindrances, the pulled rugs, the rejections, I decided to believe the book thing was the best—maybe the only—way toward resurrection, restoration, a return to a refigured and rebuilt life with reinvigorated hopes. Even if the hope should prove another self-deception, it might still serve for a while as ballast. But was the ballast in a rising balloon or in a sinking ship?

• • •

About this time I became susceptible to seeing coincidences related to the manuscript as encouragement from some beyond, a notion perhaps arising from Jack’s oft-repeated story about his wife’s temporary postpartum psychosis. As she lay in a hospital bed, she saw divine figures issuing from an empty light socket and a hissing radiator, and she kept delfically repeating, “The coincidences! The coincidences!”

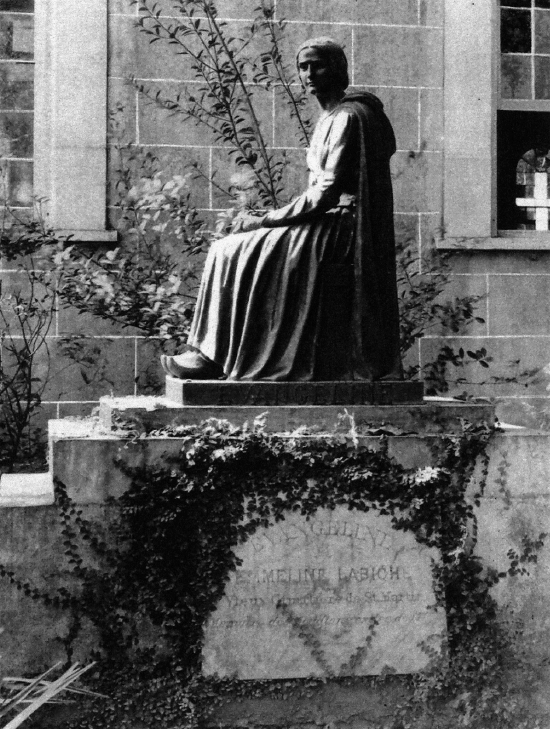

One night after writing about St. Martinville, Louisiana, and the statue there of Longfellow’s Acadian heroine, Evangeline—a sculpture that Hollywood star Delores Del Rio allegedly had posed for during the filming of the 1929 movie Evangeline—I idly mentioned to Jack I had no idea what the actress looked like. I needed to go to the library to check the truth of the story. He never approved research pushing aside writing because writing to him meant only words flowing forth. For him, looking something up other than a spelling was procrastination. A writer of fiction, he was on occasion correct.

Jack grumbled but then cut his remonstrance short as he, a lover of old movies, remembered among the few books on his shelves one about cinema, but in French and containing a mere dozen or so photographs. He, of poor memory, recalled it only because his wife (she of “The coincidences!”) had been reading the history and left it on a table behind the couch. I suggested a long shot of looking in the book just to see if there truly was a film made from Longfellow’s narrative poem “Evangeline,” starring Delores Del Rio. Jack went to the table, picked up the history. Without his turning a page, the book fell open to a sepia photograph of three actors. I pointed at one. Who’s that woman? He moved closer to a lamp and bent to read the French caption. “Curious,” he said and looked again. Shaking his head, “Is this the face on the St. Martinville statue?” I pushed the book under the light. She looks like it. “That woman,” he said, “that is Delores Del Rio.”

Always hostile to anything beyond rational explanation—like relevant, clustered coincidences—Jack said, “I must admit this is unusual,” and for years afterward he talked of the incident. But for a week or two, I, also a rationalist, chose to believe what I was writing would find a publisher. Didn’t some Great Incomprehensible have it ordained?

(When I was writing of this incident, I picked up a history of Louisiana, this one of eight hundred pages, to look for a picture of the statue, the book opened as if of its own accord, directly to a photograph of the bronze Evangeline. Six times I tried to repeat it, and each time I failed to find her again.)

• • •

People of the Middle Ages saw human existence as a Great Wheel continually turning. Fortuna, the goddess of Fate, grantor of prosperous voyages, bringer of fertility, kept her wheel moving to carry a life forward, upward, downward, onward, outward, inward, upside down, topside up. No sooner soaring than sinking. Flush today, flat broke tomorrow. Fortune and misfortune in ceaseless gyration, alternation, flux and reflux, ascent and descent, coming, going. Oops! Bingo! Oops! Bingo! Every turn headed toward a return, the rotations ending only with death.

My writing life was recasting me as a medieval man, and why not? The Great Wheel assured that falling, failing, was only precursor to rising, realizing. I made a copy of a sixteenth-century illustration from my one-volume Shakespeare, and for months to come I kept it at hand to remind me.

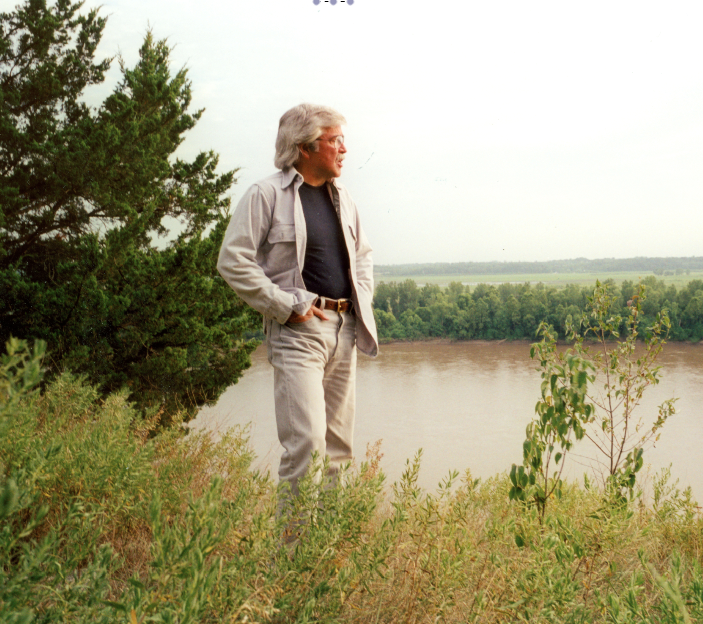

William Trogdon, who writes under the name William Least Heat-Moon, was born of English-Irish-Osage ancestry in Kansas City, Missouri. He holds a bachelor's degree in photojournalism and a doctorate in English from the University of Missouri. Among his writing credits, he is the author of Blue Highways, which spent 42 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list in 1982-83. William Least Heat-Moon lives and writes outside Columbia, Missouri.

William Trogdon, who writes under the name William Least Heat-Moon, was born of English-Irish-Osage ancestry in Kansas City, Missouri. He holds a bachelor's degree in photojournalism and a doctorate in English from the University of Missouri. Among his writing credits, he is the author of Blue Highways, which spent 42 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list in 1982-83. William Least Heat-Moon lives and writes outside Columbia, Missouri.

"A Guy in a Metal Suicide-Box," chapter six of Writing Blue Highways, is reprinted here by permission from the University of Missouri Press and the author.