Essay by Carol Dorf

Why Choose? There's Plenty of There There

Like children shuttling between the homes of divorced parents, American poets feel obliged to negotiate poetic lineages. In the twentieth century, anthology editors often aligned poets with Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman. More recently, Gertrude Stein ("a rose is a rose is a rose") and William Carlos Williams ("this is just to say I have eaten the plums") are the parents we're asked to choose between.

Stein (1874-1946) and Williams (1883-1963) are back in vogue. Stein's role as a collector has been highlighted in a show of her family's art collection called The Steins Collect, which I saw in San Francisco this year. (It's currently in Paris and will head to the Met in New York in 2012.) Her writing has been presented in related side exhibits and revival performances.

Stein (1874-1946) and Williams (1883-1963) are back in vogue. Stein's role as a collector has been highlighted in a show of her family's art collection called The Steins Collect, which I saw in San Francisco this year. (It's currently in Paris and will head to the Met in New York in 2012.) Her writing has been presented in related side exhibits and revival performances.

Meanwhile, Williams's longtime publisher, New Directions, has just released By Word of Mouth, a compilation of his translations of Spanish poetry. And the University of Iowa Press has published Visiting Dr. Williams, an anthology of contemporary poetry that emphasizes his continuing influence.

Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. As a small child, she moved between Vienna and Paris before her well-to-do German-Jewish family landed in Oakland, California. Her first languages were German and French. Although she had little formal education as a child, she was admitted to Radcliffe College, where she graduated magna cum laude. She then studied medicine at Johns Hopkins before settling in Paris.

For many, she is best known for her salons and support of other artists, including Picasso, Gris, Matisse, and Hemingway. She's also a lesbian foremother—a woman who boldly declared herself a genius—with her own supportive wife, Alice B. Toklas. In fact, Stein's 1933 The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is her most accessible book. Uncharacteristic in style but a very enjoyable read, it conveys a good sense of her life at the time.

Williams grew up in Rutherford, New Jersey, and trained to be a doctor, which became his lifelong profession. During his time in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, he met two other major modernist poets—Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)—and began writing poetry.

Williams grew up in Rutherford, New Jersey, and trained to be a doctor, which became his lifelong profession. During his time in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, he met two other major modernist poets—Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)—and began writing poetry.

Like Stein, Williams was the child of immigrants. His father was English and his mother Puerto Rican, of Basque and Jewish descent. He spent a year in Geneva and Paris as a teenager. In his autobiography, Williams notes:

Spanish and French were the languages I heard habitually while I was growing up. Mom could talk very little English when I was born, and Pop spoke Spanish better, in fact, than most Spaniards.

While their work is very different, Stein and Williams had a surprisingly similar agenda. Both saw themselves as creating distinctly new American idioms. (Stein even titled her 1925 family epic The Making of Americans.) As writers for whom English was a second language, they were acutely aware of its nuances and the differences between American English and British English. On separate trajectories, they created poetry that was inspired by spoken language rather than printed texts.

To my mind, reading these poets should be a case of both, and—not an exclusive or. Yet, some poets fiercely hew to one or the other, partly because the work of Stein and Williams can be used to bolster different contemporary poetic schools of thought.

In her creative writing and essays, Stein's focus was on syntax. Here's what she says in her 1935 essay "Punctuation in Prose":

The question mark is alright when it is all alone when it is used as a brand on cattle or when it could be used in decoration but connected with writing it is completely entirely completely uninteresting. It is evident that if you ask a question you ask a question but anybody who can read at all knows when a question is a question as it is written in writing.

For Stein, writing is an intimate conversation between reader and writer. The reader enters the text as a person who knows the writer, knows when a question is actually a question, and when it is something else entirely.

Language poets like Lyn Hejinian see her as a standard-bearer for complexity despite Stein's explicit desire to simplify the language. In her own book-length prose poem My Life, Hejinian follows what she sees as Stein's project of embracing contradiction in a continuous stream of conversational language. Hejinian said of Stein in a 1995 interview:

[H]er work is irreducible and unsynopsizable, because for every proposition that she makes, she also makes counter-propositions; her whole project is an enormous and spreading study of the relationships of everything to everything else....

Hejinian provides important insights into Stein's work, but such criticism is not an encouraging entry point for most readers. For me, the best way to read Stein is aloud, as poetry, ideally with a friend, and focusing more on sound than on linear sense.

Hejinian provides important insights into Stein's work, but such criticism is not an encouraging entry point for most readers. For me, the best way to read Stein is aloud, as poetry, ideally with a friend, and focusing more on sound than on linear sense.

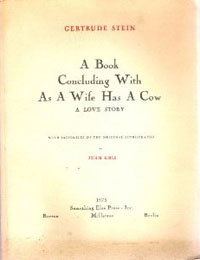

For example, Stein's 1926 A Book Concluding with As a Wife Has a Cow embraces the domestic and has wonderful illustrations by Juan Gris. Take the short poem “Happen to Have,” which provides a different experience when spoken than when read:

Happen To Have.

She does happen to have an aunt and in visiting and in taking a flower she shows that she is well supplied with sweet food at home otherwise she would have taken candies to her aunt as it would have been her sister. Her sister did.

In contrast, the work of William Carlos Williams appears more accessible on the surface. Here is the start of "Landscape with the Fall of Icarus" in his 1962 Collected Poems:

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was springa farmer was ploughing

his field

Williams's short lines allow the reader to pause in order to take in the tragic impact of Icarus's fall in the context of everyday life. The final lines:

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

His use of understatement, with those short lines rooted in quotidian details, has often been parodied. Try googling "this is just to say," or "A Red Wheelbarrow." Jack Spicer's parody opens like so:

Rest and look at this goddamned wheelbarrow. Whatever

It is.

Parody, imitation, conversation: These are the ways we bring the work of a poet like Williams into our own writing. A quick sampling of the poets in Visiting Dr. Williams includes Philip Levine, Denise Levertov, Robert Creeley, and Rane Arroyo. Levertov's tribute, "Williams: An Essay," ends:

He loved the lotus cup, fragrant upon the swaying water, loved the wily mud pressing swart riches into its roots, and the long stem of connection.

The connection of contemporary writers to both Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams is ongoing and powerful. My sidebars below provide starting points for reading the two poets, and you can decide for yourself if you must declare an alliance. Given the creative impact of both Williams and Stein, I'd rather just travel in each of their landscapes and enjoy rediscovering the pleasures of their writing.

Reading William Carlos Williams

To see how engrained Williams's style is for many American poets today, read his classic poem about plums, "This Is Just to Say," and then write a parody of it. Here’s a link to the original by Williams, followed by links to two parodies:

To see how engrained Williams's style is for many American poets today, read his classic poem about plums, "This Is Just to Say," and then write a parody of it. Here’s a link to the original by Williams, followed by links to two parodies:

- “This Is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams

- "The Hazards of a Later Era" by Ed Dorn

- "Variations on a Theme by William Carlos Williams" by Kenneth Koch

And here is my own version:

Because You Told Me (Not) To

I ate the asparagus

which a sensible person

would have saved

for dinner.The stalks were perfect—

crisp-tender.

They reminded me

of your temper.And of spring,

so I won't

apologize.

But, thanks.— Carol Dorf, 2011

Reading Gertrude Stein

On the American Academy of Poets' website, you can hear Lyn Hejinian read "A Light in the Moon" from Stein's 1914 book of prose poems Tender Buttons. Better yet, click on "A Light in the Moon" and read it aloud yourself.

This poem will have you reflecting on the moon, decisions, sleeping on decisions, music, and nearly everything else in the minute it takes to read the paragraph. At the American Academy's site (poets.org), you'll find other poems from Tender Buttons that evoke the playful twists of her spoken language.

This poem will have you reflecting on the moon, decisions, sleeping on decisions, music, and nearly everything else in the minute it takes to read the paragraph. At the American Academy's site (poets.org), you'll find other poems from Tender Buttons that evoke the playful twists of her spoken language.

Penn Sound of the University of Pennsylvania takes us to the master herself. What better way to learn to read Stein than to hear her reading her own works? Be sure to listen to "A Valentine to Sherwood Anderson."

Stein's writing, of course, is often viewed as forbidding. I've wrestled with it myself, but I also know that it's not just "experimental" or "opaque." Beyond hearing Stein's words spoken aloud, Renate Stendhal's Gertrude Stein in Words and Pictures (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994) offers another approach to reading Stein. Stendhal mixes photographs from Stein's life with short excerpts of her writing to provide biographical context.

As the modernist visual artists she championed reordered our sense of space, Gertrude Stein changed the way we see narrative. And she viewed herself primarily as a writer, not as an art patron. For most of her life, she spent the hours from midnight to dawn writing. She liked to go to bed before the birds began singing, but at times her writing was so energizing she continued into the early morning.

Publishing Information

- The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde, San Francisco MOMA, May 21 to September 6, 2011. Also see The Steins Collect, the exhibition book, edited by Janet Bishop et al. (Yale University Press, 2011).

- By Word of Mouth: Poems from the Spanish, 1916–1959, translated by William Carlos Williams (New Directions, 2011).

- Visiting Dr. Williams: Poems Inspired by the Life and Work of William Carlos Williams, edited by Sheila Coghill and Thom Tammaro (University of Iowa Press, 2011).

- The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein, originally published in 1933 (Modern Library, 2000).

- The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams, originally published in 1951 (New Directions, 1967).

- The Making of Americans by Gertrude Stein, originally published as a 900-plus-page book in 1925 (Dalkey Archive Press, 1995).

- "Punctuation in Prose" in Lectures in America by Gertrude Stein, originally published in 1935 (Beacon Press, 1985).

- "Roughly Stapled: An Interview with Lyn Hejinian" by Craig Dworkin, Idiom #3, 1995.

- My Life by Lyn Hejinian, originally published in 1980 (revised edition, Sun and Moon Press, 1987; Green Integer, 2002).

- A Book Concluding with As a Wife Has a Cow: A Love Story by Gertrude Stein with lithographs by Juan Gris, originally published in 1926 (Ultramarine Publishing, 1992).

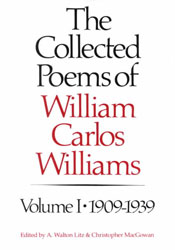

- “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” in Collected Poems: 1939-1962, Volume II by William Carlos Williams (New Directions, 1962).

- Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein, originally published in 1914 (ReadaClassic, 2010).

Art Information

- Portrait of Gertrude Stein by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1913; George Eastman House Collection; public domain

- William Carlos Williams (date unknown); public domain

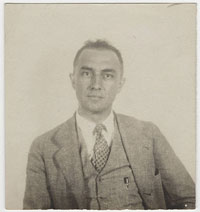

- William Carlos Williams (circa 1920; “believed to be passport photograph”); Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; public domain

- Portrait of Gertrude Stein by Carl Van Vechten, 1934, New York; Van Vechten Collection, Library of Congress; public domain

Carol Dorf is the poetry editor at Talking Writing.

Carol Dorf is the poetry editor at Talking Writing.

Carol began thinking about Gertrude Stein after she saw The Steins Collect exhibit at SFMOMA in San Francisco in June 2011. "The current fascination with Stein as a ‘collector’ troubles me," she says. Of the exhibit, Carol adds:

“While I loved seeing many of the paintings she and her siblings collected (like Picasso's portrait of Stein or Matisse's ‘Woman with a Hat’—what's not to love?), I found it odd that a major writer was portrayed primarily in terms of the objects she owned.

“A reading of Stein's work was held in the atrium, essentially a large hallway that visitors traverse on their way to the exhibits, and there were no chairs. The readers (almost all straight, almost none Jewish) were nearly inaudible, even to those of us who found a spot on the floor near the podium."