By Lorraine Berry

Traveling Far between the Covers of Caleb’s Crossing

![]() When I was a kid, my step-grandfather drove what the English called a “coach” but what is more generally known in the U.S. as a tour bus. It’s the first time I can remember hearing the term “busman’s holiday”—though at the time, I didn’t have a clue what it meant.

When I was a kid, my step-grandfather drove what the English called a “coach” but what is more generally known in the U.S. as a tour bus. It’s the first time I can remember hearing the term “busman’s holiday”—though at the time, I didn’t have a clue what it meant.

Then I went to graduate school to become an historian. I never had time to read for pleasure, except over winter and summer breaks. And what did I read then? Big, fat historical novels, such as Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose or Foucault’s Pendulum, or Sharon Kay Penman’s magnificent Here Be Dragons—which gave me a guide to follow as I traveled around Wales and imagined how it had looked in the thirteenth century. Basically, each summer would be my own busman’s holiday, as I read fictionalized accounts of the things I knew I already loved.

Geraldine Brooks captured me with her first novel, Year of Wonders, in which she spun gold out of the dross that was the Bubonic Plague. I followed her further with March, her Pulitzer Prize-winning imagining of the Civil War from the frontline perspective of the missing patriarch of the Little Women family. I didn’t love People of the Book, however, so Caleb’s Crossing, her latest, didn’t come with a guarantee of my enjoyment.

Geraldine Brooks captured me with her first novel, Year of Wonders, in which she spun gold out of the dross that was the Bubonic Plague. I followed her further with March, her Pulitzer Prize-winning imagining of the Civil War from the frontline perspective of the missing patriarch of the Little Women family. I didn’t love People of the Book, however, so Caleb’s Crossing, her latest, didn’t come with a guarantee of my enjoyment.

The book returns Brooks to the form I like best: historical fiction that imagines a life without recreating it in plodding detail—this time, in a seventeenth-century village on Martha’s Vineyard. Bethia Mayfield is a minister’s daughter who longs for a life of the mind, which she surreptitiously pursues by listening in on her brother’s lessons with her father in Latin, Greek, and Biblical exegesis. But she can’t stop herself from demonstrating that she has learned more than her brother:

At first, when I gave out a Latin declension, father was amused, and laughed. But my mother, working the loom as I spun the yarn, drew a sharp breath and put a hand up to her mouth. She made no comment then, but later I understood. She had perceived what I, in my pride, had not: that father’s pleasure was of a fleeting kind—the reaction one might have if a cat were to walk about upon its hind legs.

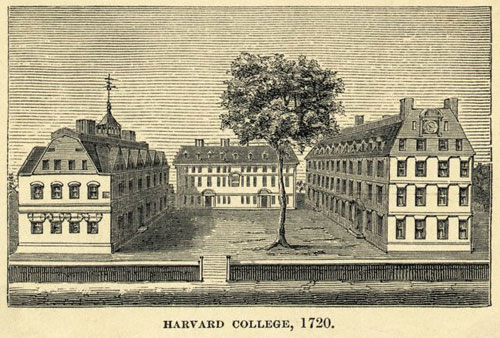

As a young, restless teen, Bethia wanders the island and meets Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, a member of the Wopanaak tribe, who becomes her friend. Through a series of events, Caleb comes to live with Bethia’s family and eventually becomes the first Native American admitted to Harvard College.

Brooks bases the entire novel on brief mentions of Caleb’s achievement and on the one surviving document in Caleb’s hand. In this way, Caleb’s story reminds me of the Italian academic practice of microstoria, known in English as microhistory, which tells the tale of a single individual or village based on what historical fragments may be remaining. (Perhaps the best known of these histories to American readers is Natalie Z. Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre.)

Microhistories were (and remain) my favorite form of historical writing because they put the common individual at the center of a history—rather than its margins—and Brooks’s ability to perform this type of magic is mesmerizing. Caleb’s story interweaves the politics of Calvinist divines, the rivalry among tribes, the competition between “religion” and “magic,” and, of course, the desire by those excluded from the academic life (anyone who wasn’t a white man) to participate in the life of the mind.

Brooks also gives Bethia a consciousness of beauty, which she expresses in her writing and which drew me further into the book:

Since I was born here, I too have come to feel that I am a person of the first light, perched at the very farthest edge of the new world, first witness to each dawn of the turning globe. I count it no strange thing that one may, in a single day, observe a sunrise out of the sea and a sunset back into it, though newcomers are quick to remark how uncommon it is. At sunset, if I am near the water—and it is hard to be very far from it here—I pause to watch the splendid disc set the brine aflame and then douse itself in its own fiery broth.

Waves of story, some set on Martha’s Vineyard, some at Harvard, roil and crash together, creating a maelstrom of passion, politics, love, and the specter that haunted Native and White alike: the omnipresence of death in an age when neither religion nor magic could fight disease and disaster.

The British writer L.P. Hartley once wrote: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” As someone who will not get to travel this summer—obliged as I am with writing (and, oh yeah, no money)—I will take my pleasures getting lost in prose about places long ago but not so far away.

Publishing Information

-

Caleb’s Crossing by Geraldine Brooks (Viking Press, 2011)

Lorraine Berry is a contributing editor at Talking Writing.

Lorraine Berry is a contributing editor at Talking Writing.

Of her summertime plans, she says, "I will spend the summer working on a manuscript for a Hollywood producer who has bought the rights to a story I wrote. When I'm not writing, I will be found either in the woods or sitting on the edge of the creek, hoping to avoid losing my toes to a snapping turtle."