Editor’s Note by Martha Nichols

We Wrestle with Ideas—and Rabid Publicists

Okay, I’m biased. I love reading and writing reviews. I’ve been a book reviewer and editor for decades, and journals like the New York Review of Books have been my preferred nonfiction reading since college. It’s the way I think, picking apart things to figure out how they work.

Increasingly, though, I’ve felt the need to justify my existence as a critic. Post-2000, the field is overrun with “likes” and star ratings. The onslaught of reviewing online mixes the work of professional critics with everyone from the author to paid-for puffery to genuine fans. I’m all for breaking down the old gates to publishing, but once groupthink takes over, popularity rules. Flash a thumb’s up, or you’re a hater.

This issue of Talking Writing explores what it means to be a critic in the age of self-publishing and peer reviewing. We’ve got Goodreads now; new book blogs seem to pop up every second. Few readers will be shocked to hear that traditional literary criticism is dying. The question is, should we revive it—and if so, in what form?

Even before the populist revolution online, there were good reasons to question a literary establishment dominated by white male voices. I’ve been affiliated with the Women’s Review of Books for twenty years because I believe writing by women and authors of color deserves far more critical attention. As for reviews in blogs and Goodreads, many provide insights about plot, characters, and artistic impact—the staples of literary criticism—and are far from logrolling raves.

But that doesn’t justify killing off professional critics, whether they’re academics or experienced creative writers and journalists. Given the popularity of Top Chef and Project Runway, TV viewers clearly accept “master chefs” and fashion designers as experts. Yet, when it comes to literature, apparently everyone’s a critic now, just as everyone’s a writer—and who needs those snarky experts? The old infrastructure for evaluating literature is crumbling beneath my feet, and not for the right reasons.

The outcry against “mean” reviews is one sign of the literary expert’s fall from grace. For years, there’s been debate about the ethics of going negative—at least as far back as the 2002 Dale Peck review that opened with “Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation.” But the rise of the Twitterverse has upped the stakes: In 2012, when critic William Giraldi smacked down an Alix Ohlin novel in the New York Times Book Review, it generated a storm of tweets like “one of the meanest NYTBR reviews I've seen”—as if Ohlin, a princess in her tower, needed protection from the critic ogre.

Giraldi’s crime? Harshly judging a book because it failed for him as literary art.

Last November, when Isaac Fitzgerald, a former director of publicity at McSweeney’s, was named Book Editor at BuzzFeed, he told one interviewer he’d run no negative reviews: “Why waste breath talking smack about something? …You see it in so many old media-type places, the scathing takedown rip.” He claimed that today’s readers know books are “something that people have worked incredibly hard on, and they respect that. The overwhelming online books community is a positive place.”

To be fair, this interview with Andrew Beaujon at Poynter sparked a hilarious backlash of online commentary. In a Washington Post blog, Alexandra Petri provides her own BuzzFeed-style edits of “10 famous mean book reviews,” including:

This is not a book to be tossed aside lightly.

It should be hurled with great force. (Dorothy Parker)

Bad reviews are more fun to read—but there’s nothing wrong with that. As an editor, I want provocative book reviews to go viral and get talked about; I want readers to be hooked by literary questions, just as so many are by culinary debates about too much salt or whether the duck breast is undercooked. Hard-asses like Parker and Peck and bad-boy chef Anthony Bourdain are a kick; it’s also why their criticism gets read. More to the point, by insisting on quality—of food or writing—they make discussions about creativity and craft part of the public conversation.

I love arguing about ideas, and I worry that too many people are losing their ability or desire to do so. The TW contributors in this “critics” issue don’t all agree with me, and I wouldn’t want them to. Instead, they explore the theme from a variety of angles—such as “Literary Criticism Is Dead” by Ron MacLean and, later in the issue, “Why Mainstream Critics Fail Writers of Color” by Aimee Phan.

TW Winter 2014 also includes a number of “My Favorite Critic” essays, a series that conveys the subjective thrill of reading great criticism. In “How a Literary Critic Slapped Me Awake,” David Meischen describes the way a controversial essay by critic Leslie Fiedler changed his perception of Moby Dick and the world. Other TW contributors will focus on George Orwell, Zadie Smith, and Carolyn Heilbrun, among others.

I have many favorite critical essayists myself, including Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Joseph Brodsky. Writers writing about writing—as these and many other authors do—create what we mean now by literary criticism. To dismiss it as overly intellectual or "mean" or "old media" is to ignore why a passionate attachment to literature is worth fighting for.

Our annual poetry spotlight in TW Winter 2014 is a tribute to Muriel Rukeyser, and it’s hard to think of a more passionate advocate for poetry and its value to society. During the course of this issue, TW will publish eight poets, including Alicia Ostriker and Katharine Harer, who engage with the same mix of political concerns, humanitarian values, and sensuous life found in Rukeyser’s poems.

In her 1949 book of criticism, The Life of Poetry, Rukeyser exhorted readers to get over their fear of and resistance to poetry—to be a “witness,” to choose “the act of seeing or knowing by personal experience, as well as the act of giving evidence.”

In the same way, I believe today’s literary critics need to witness all that art evokes in human beings, be it joy, rage, hurt, or sorrow. As Rukeyser wrote, “The only danger is in not going far enough”:

If we do not go deep, if we live and write half-way, there are obscurity, vulgarity, the slang of fashion, and several kinds of death. All we can be sure of is that our art has life in time, it serves human meaning, it blazes on the night of the spirit…. For this is the world of light and change: the real world; and the reality of the artist is the reality of the witnesses.

Publishing Information

- “The Moody Blues” (review of Rick Moody’s The Black Veil) by Dale Peck, New Republic, July 4, 2002.

- “Peck the Knife” by Laura Kipnis, Slate, July 7, 2004.

- "William Giraldi, Literary Bad Boy" by Martha Nichols, Talking Writing, August 24, 2012.

- “BuzzFeed Names Isaac Fitzgerald Its First Book Editor” by Andrew Beaujon, Poynter, November 7, 2013.

- “10 Famous Mean Book Reviews, Edited for Buzzfeed Books’ New Positive-Only Policy” by Alexandra Petri, Washington Post, November 7, 2013.

- The Life of Poetry by Muriel Rukeyser, originally published in 1949 by Current Books (Paris Press, 1996).

Art Information

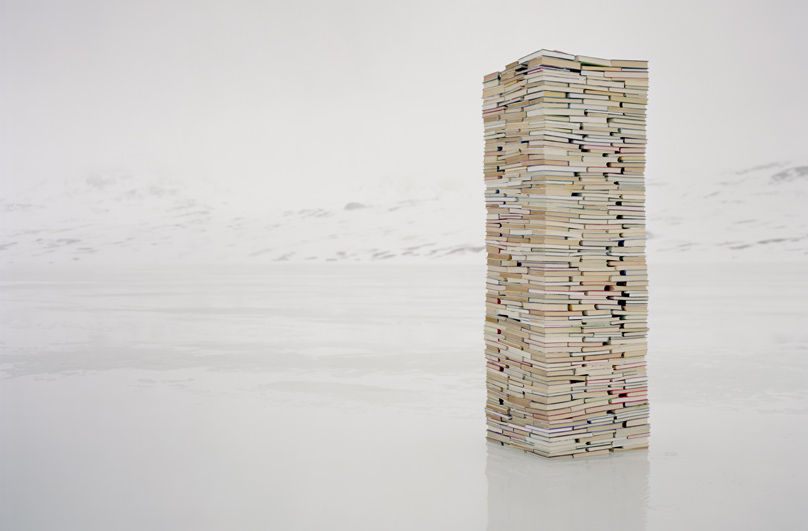

- "Discipline Considered an Option" © Rune Guneriussen; used by permission.

- "Bushy Edges of Fiction" © Rune Guneriussen; used by permission.

- "Statistics of Progression" © Rune Guneriussen; used by permission.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. Her most recent essay in Women’s Review of Books, “A Profound Absence” (November/December 2013), focuses on the continuing lack of female intellectual voices in mainstream media.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. Her most recent essay in Women’s Review of Books, “A Profound Absence” (November/December 2013), focuses on the continuing lack of female intellectual voices in mainstream media.

Martha confesses that she’s never been a fan of academic criticism: "Many years after my first English lit class, the word ‘semiotics’ still makes me cringe.”

But as a devotée of Top Chef—one who loves snipes by Anthony Bourdain such as "baby vomit and wood chips" or “it was like putting my nose into a campfire” —she's long contemplated what Top Author might be like. Suggestions, anyone?