TW Interview by Mara Araujo

A Dystopian Short Story Writer Who Loves—and Fears—Nature

In Diane Cook’s “The Mast Year,” Jane is having an exceptionally great time—or at least that’s what she's led to believe. She’s surprised with a promotion; she gets engaged. But she also gains the devotion of crowds of strangers who camp outside her home. The only explanation given comes from Jane’s mother, who tells her she's experiencing a “mast year,” likening it to an annual cycle when trees produce more nuts or fruit than usual. The crowds soon become perpetual spectators, observing Jane's every move, cheering her on as she “peers out of windows.”

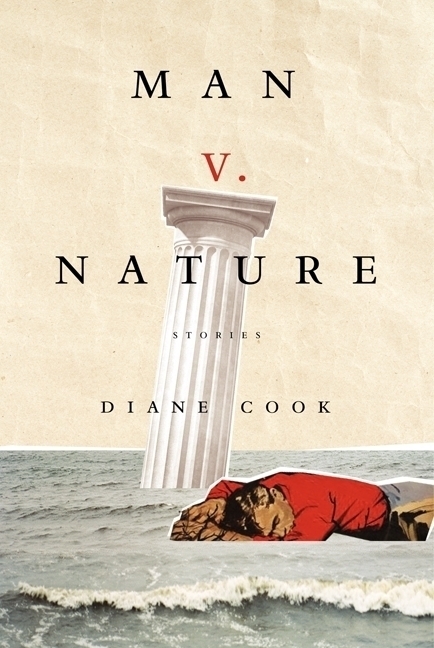

This short story falls near the end of Man v. Nature, Cook’s 2014 prizewinning collection (HarperCollins). It’s her first book, although some of the stories appeared previously in Guernica, Tin House, and Granta.

This short story falls near the end of Man v. Nature, Cook’s 2014 prizewinning collection (HarperCollins). It’s her first book, although some of the stories appeared previously in Guernica, Tin House, and Granta.

“Reality can be strange in very small ways,” Cook told me during our interview this February. That’s an accurate assessment of the way her off-kilter stories allow me to see the oddity of my own world. In “these lively, apocalypse-tinged tales,” reviewer Robin Romm notes of Man v. Nature in the New York Times Book Review, “Cook mines the moments that precede the losses—when the battles are truly raging—and it’s in them that she finds great beauty and strangeness.”

In “Somebody’s Baby,” mothers are forced to endure a world in which their babies are stolen. All it takes is one seemingly innocent moment of distraction for a man to come in and snatch their children. When one mother’s baby is taken, she’s left with the ultimate question: “If you could suddenly get back everything you’d already said goodbye to, would you want it?”

Cook is a former radio producer for NPR’s This American Life, where she worked from 2001 to 2007. She says one of her favorites episodes is “My Pen Pal” from 2003, which relates stories about "people whose relationship could not exist without the help of the postal service,” according to the This American Life website. Another is “In the Shadow of the City” from 2006, featuring stories about peculiar places that lie “on the edge of civilization.” Cook told me she enjoyed her producing work because the stories were “complicated puzzles to put together.”

I spoke with her for close to an hour by phone. In the Boston area, snow was piled high around my house, with a curtain of giant icicles hanging from my window. Cook was across the country in Sisters, Oregon, looking at the three nearby Three Sisters peaks the city is named for and enjoying unusually warm weather.

Still, it wasn’t hard to imagine her forging through the dark New Hampshire forests, as she's done in the New England Literature Program (NELP) for the University of Michigan. Students live at Camp Kabeyun on Lake Winnipesaukee, immersing themselves in books by New England Transcendentalists like Henry David Thoreau. Cook has participated in NELP as both a student and teacher; she last taught there in 2012.

She's an engaging presence who jokes about her “amateur birding” ways. Her youthful and throaty voice surprised me; given the disturbing undertones of her stories, I'd expected her to sound older, even intimidating. But Cook's relaxed demeanor made it easy to ask about her literary influences and unique writing habits, including the impact of new technology like the always handy iPhone Notes app.

This TW interview has been condensed and edited.

TW: What do you like about nature writing?

DC: I feel transported to places I actually want to be. When I think of going on vacation, it's always to a national park or a wild place. I appreciate, too, when nature writing says something about the people observing the natural world—in Thoreau’s Walden, for example. Part of why classic nature writing feels so classic is that it teaches us about ourselves. I feel like a better human after I read really good accounts of being in the wilderness or accounts of how natural systems operate.

TW: Do you think the genre has changed over the past decade?

DC: I don't know how nature writing is changing necessarily, but I feel like the natural world is shown more and more in fiction—in stories of people, especially with apocalyptic or dystopian types of storylines. There's more of this clash of people with nature. Nature writing is expanding in new ways or going back to the reverent but fearful way people used to write about the natural world.

TW: How do you use your observations of the natural world to craft stories? Do you have a specific example of something you witnessed in nature, and then a light bulb goes off? Like, oh! I should write about that.

DC: Yes, that's how a lot of the stories in Man v. Nature came about, actually. Through thinking, reading, watching nature documentaries, or just observing the natural world. I'm mostly interested in how humans are still animalistic and whether we once had a wilder existence than we do now.

I was watching this hawk get chased around by a couple of crows. I assumed, in a really amateur, nature-observer way, that the crows were defending their territory against an interloper, and that it happens all the time. Every nature documentary you watch shows some kind struggle for survival, where the babies get preyed on by the fox that comes around and eats the eggs. And the mother can't do anything about it. She can try and ward off the predator, but at some point, she just has to give up.

If life in the wild is so precarious, I thought, what if it was more like that for people? And it is like that for some people. Life is very precarious in other parts of the world or even at certain poverty levels in this country. What if we had predators that actually would steal our babies? So, I wrote “Somebody's Baby.” Ideally, it’s more than just a scary story. For me, that story is about anxiety and motherhood.

TW: You mentioned Thoreau. Have you always been fascinated by the subject of nature, or did that come after you were exposed to authors like him?

DC: It might be a coincidental thing. For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to be in nature. I didn't even know why. I didn't grow up at camp or anything. I grew up in the suburbs. I am completely suburban. In my late teens and then definitely in college, I had this really romantic idea of nature. Then I took this literature class at the University of Michigan where we actually did go read in the woods.

It's called the New England Literature Program. It’s been around for forty years, and it happens in the spring. Forty undergraduate students go to New Hampshire, to this rustic camp that’s not in session yet, and live there for six weeks. I’ve taught there, too. I was a student, and then I started teaching there.

TW: Circle of life, huh?

DC: Yes, it's really nice. We read all these New England writers from long ago, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Thoreau, along with contemporary authors like Carolyn Chute and Ruth Stone. How does your experience of literature change when you’re in the place where it was born? How does your experience of Walden change if you're not in a classroom—you're actually on a pond, on a lake?

TW: Is any part of your writing process handwritten? We're so connected to digital devices now. If you use handwriting, does it affect your process at all?

DC: It's funny you ask that question, because at the New England Literature Program I was just talking about, one of the things the students do as soon as they show up is relinquish their technology. They give us their cell phones, their computers, their iPods, and whatever else they have for six weeks.

TW: Wow.

DC: Yeah, it's crazy. It's always been the rule of the program. When I was a student, email was a new thing, and nobody had a cell phone. You didn't give up as much as you would today, but it still felt crazy. We don't have TV? We can't listen to the radio? Now, students really detach from the world because they're usually so connected. They write in journals, basically the whole time—handwriting. That's their record, their intellectual and personal record of being there.

So, writing by hand has always been a really huge part of my process. I have this weird mix of different things I use. When I'm stuck, I have to step away from the computer, and things come more easily when I have the paper in front of me. I also have a big sheet of paper right next to my computer, too. I’m working on the computer, but sometimes, I just turn and start writing by hand.

The other thing I do, though, is when I go walking, I take notes on my iPhone. I'll be in the middle of the woods, and it's supposed to be this transcendent, natural experience, but if you run into me on the trail, I'll just be sitting there. It looks like I'm texting. I have pages of writing just in my phone, which is funny. It feels like a weird thing to be doing in the woods, but it actually works really well.

TW: It reminds me of your story "The Mast Year." Maybe it's just me, but I felt like there were a lot of references to social media in it. How do you think technology is changing the way writers, or humans in general, interact?

DC: I know social media can be really helpful to people. I'm unsure how I feel about it, though. Right now, I'm not on it. I actually had my husband change all my passwords so I couldn’t access it.

TW: What a strategy!

DC: I know! I don't trust myself otherwise. I write about people who are in some way estranged or extracted from the civilized world, and it’s hard to have so many voices in my head.

TW: Did you have social media in mind when you were writing “The Mast Year”?

DC: I didn’t necessarily have it in mind, but I did have the burden of responsibility we carry for everyone in our lives. And social media feels like a burden. Like, oh, I read this book, and I really liked it, so I better tweet about it because I owe it to someone. I owe it to someone to promote their thing or to think their kids are cute. I’m sure many people don’t approach it that way, but I tend to. It’s changing the way writers are writing and the way readers are reading. The burden, this responsibility for others and other people's expectations of you, is definitely in that story.

TW: In a 2014 interview with Hilary Leichter at Electric Lit, you say that Flannery O’Connor’s stories are something you’d enjoy having if you were stranded on an island. As I read “The Mast Year,” I got a sense of O’Connor’s strange-normal settings. How has she influenced your appreciation for the strange?

DC: I do love Flannery O'Connor. There's something about the way she writes that feels like you're in the presence of total mastery. Reality can be strange in very small ways, and still, in that smallness, you get completely wobbly. I like when the world is strange enough that you really have to pay attention, and you feel unsettled by it, and it's so subtle you don't even know why. If you think about what you're doing or where you are for long enough, it begins to look very strange. What I like about small-scale strangeness in fiction is that it does the same kind of thing for the reader. This is weird, but it's not so weird I don't understand what's going on—or so weird I need the whole world explained for me.

TW: In the same interview, you said you’re fascinated by how stories unfold and can reveal opportunities you might not have conceived at the outset. Which composition habits of yours aid this process?

DC: If I have an idea percolating, I circle it and circle it and circle it. It's very frustrating, because I keep thinking, “I'm never going to step into it. I'm never going to write it. I can't do this.” But eventually, I do. And when I do, I do it big and fast. Once I'm in, I just follow it where it goes, which makes me not pause and not second guess and not worry; I'm just doing it. The surprises come from that. I'm thinking new things I wouldn't have thought of if I’d been on a very tightly managed schedule.

TW: When you write really fast, is that when you're writing on paper?

DC: Often it starts on paper. There's something about paper that is really urgent. I start it on paper, and then once I feel like I'm not going to forget it, I'll transfer it to the computer. I'll transcribe what I wrote and start going from there.

TW: What advice do you have for writers pitching a collection of short stories?

DC: The best advice is to not worry about pitching a book of short stories until you've written a book you want to write. Especially with stories, you're going to hear a lot about how no one wants them. If you're not worrying about anyone wanting what you're doing for as long as possible, I think you'll be happier with the process of being an artist.

Publishers and editors, they’re not against stories. They'll work with what they love. You just have to find the right person. If they love it, they're going to try and sell it. But they might not love it. Some people just aren’t going to love your book. That's okay. It doesn't mean it's bad. Lots of people did not love my book. But I do, and the people who worked with me do, so that's what matters.

Just then a man sauntered into the kitchen. Like he owns the place, Jane thought, flushing with anger. She recognized him. He had a tent by her mailbox and went through her mail. She’d bought a shredder because of him. But she noticed the crowd of people in the doorway winking at her. A few gave her a thumbs-up sign, and she realized they liked this man.

—from “The Mast Year” in Man v. Nature by Diane Cook

Publishing Information

- Man v. Nature by Diane Cook (HarperCollins, 2014).

- “‘Man v. Nature,’ by Diane Cook,” review by Robin Romm, New York Times Book Review, November 7, 2014.

- "My Pen Pal" (September 12, 2003) and "In the Shadow of the City" (February 3, 2006), This American Life.

- “It’s Us v. Us,” interview by Hilary Leichter, Electric Lit, October 16, 2014.